Belief, Religion, Festivals

Akhari Puja

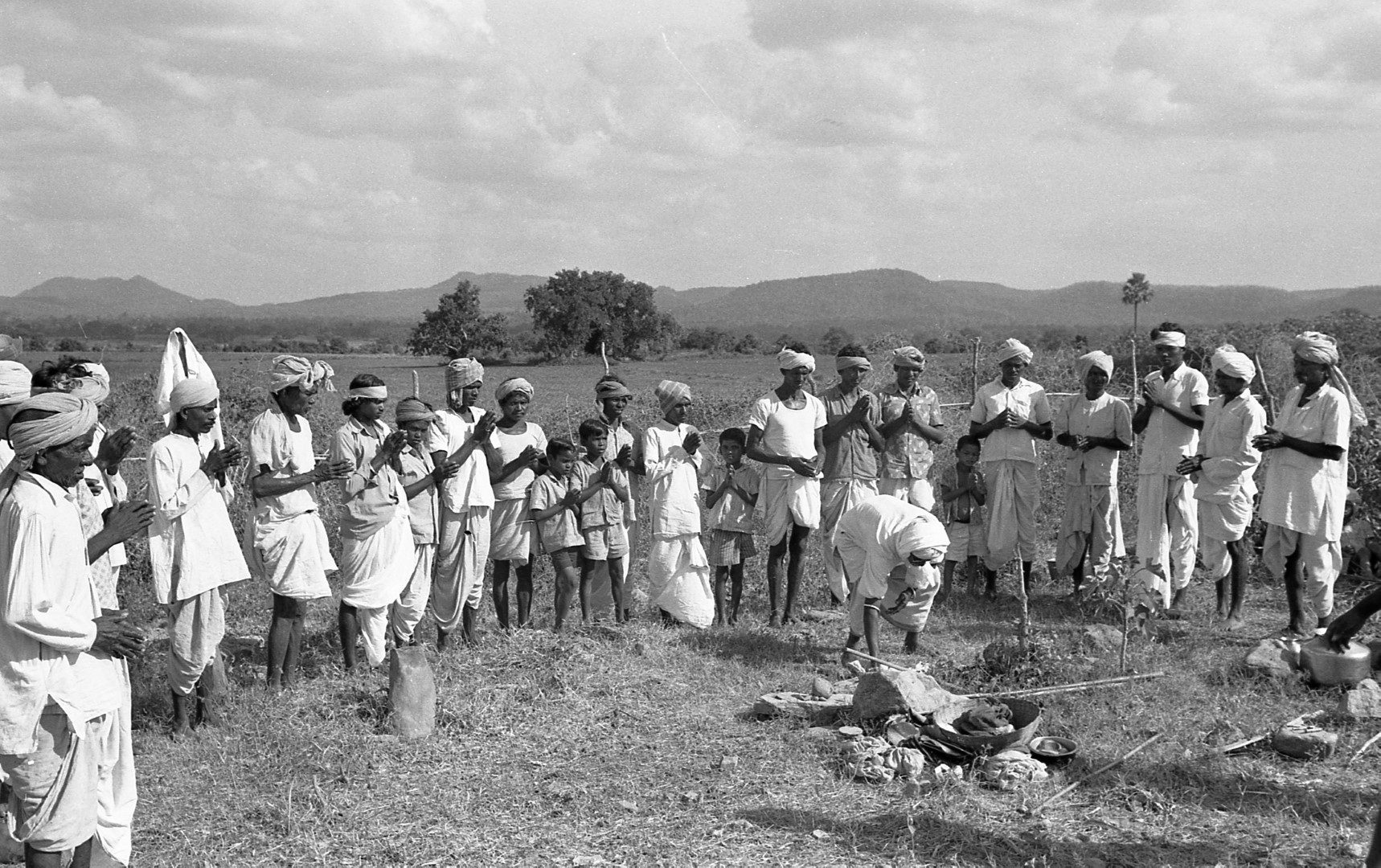

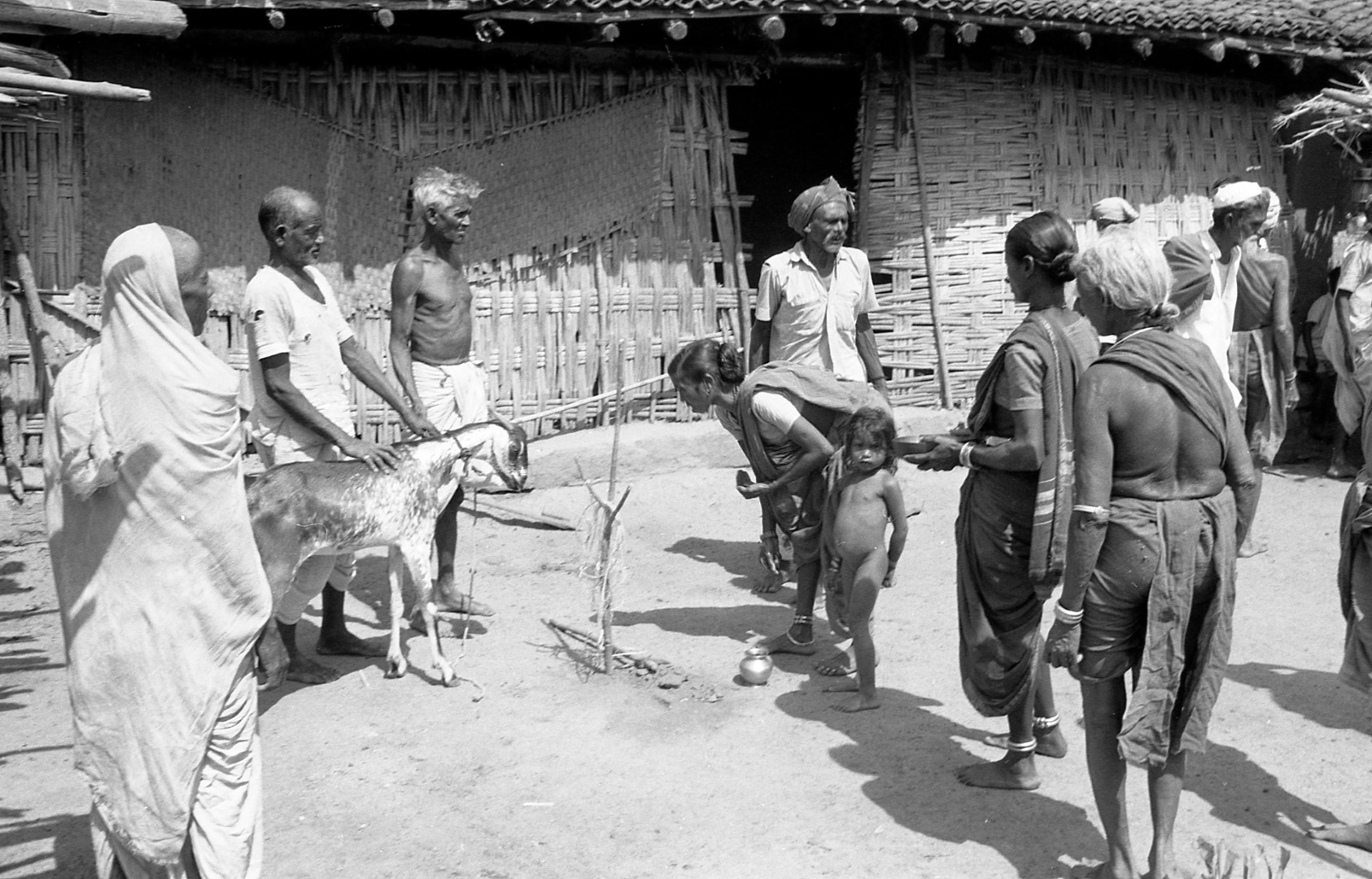

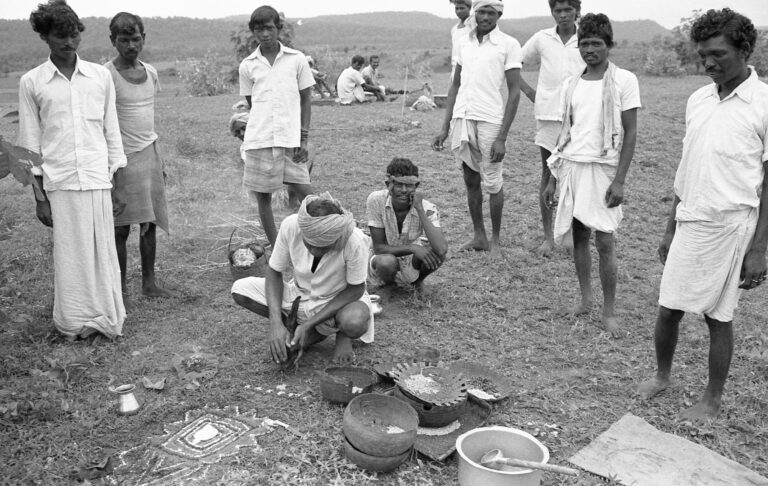

On the full moon day of Bhur Bhave, in June or July, when the forests are lush and green, the villagers go to a shrine on a path leading from the village to the forests, where the cattle are taken to graze every day. The day before, the assembled cattle and goats are kept in the forest overnight.

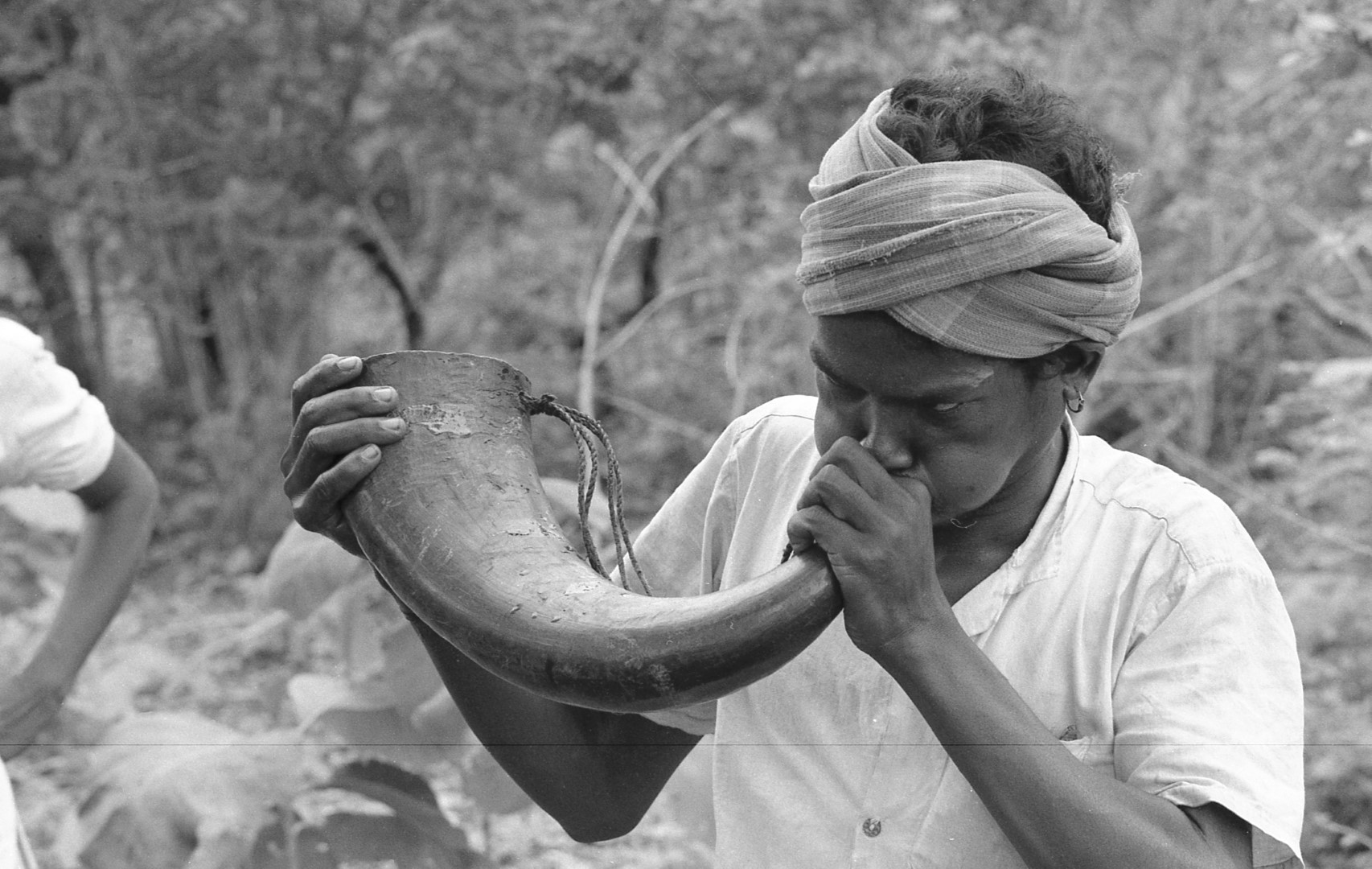

Next day a small shrine is prepared beside the forest path. It is adorned with all the village’s cattle halters and bells, which normally let the herd boys know where the cattle are grazing. The shrine is dedicated to ‘Siwa Auwal’, the goddess of the village boundary. A goat and a chicken are sacrificed to her. Prayers are sung by the assembled cattle owners, herdsmen and boys. Then a loud bison horn trumpet is blown calling the herd of cattle to be brought back to the village.

As they stream past the shrine everyone lets out a cry of joy. The cattle and the herdsmen are now felt to be protected and safe for the coming year. Rather than the plough bullocks, which are protected at the Pola ceremony, this concerns the female breeding and milking cows, another essential economic source of village’s wellbeing.

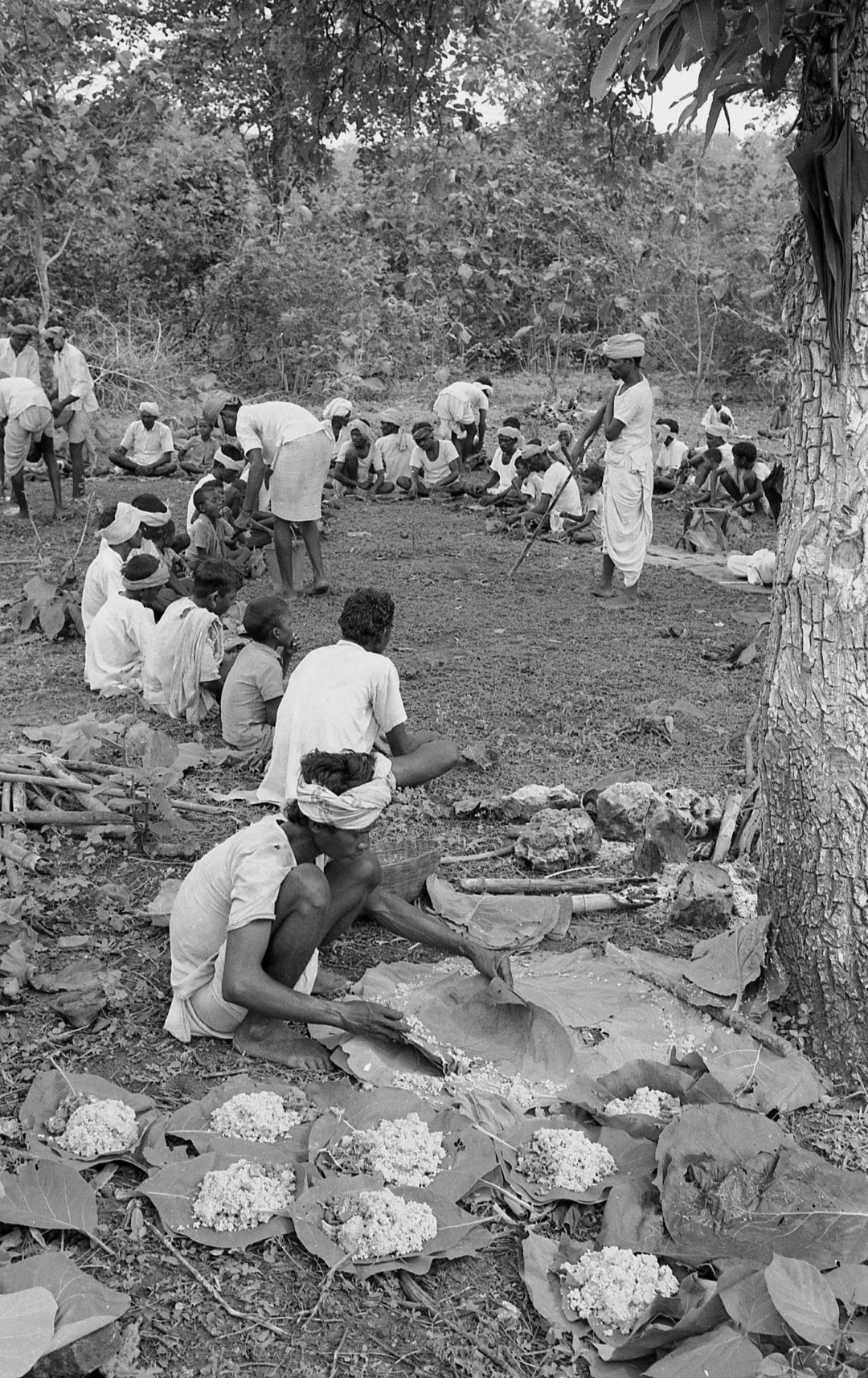

A feast of sorghum, jawaar, and sacrificed chicken and goat meat is prepared and all the herdsmen and boys enjoy a meal of thanksgiving.

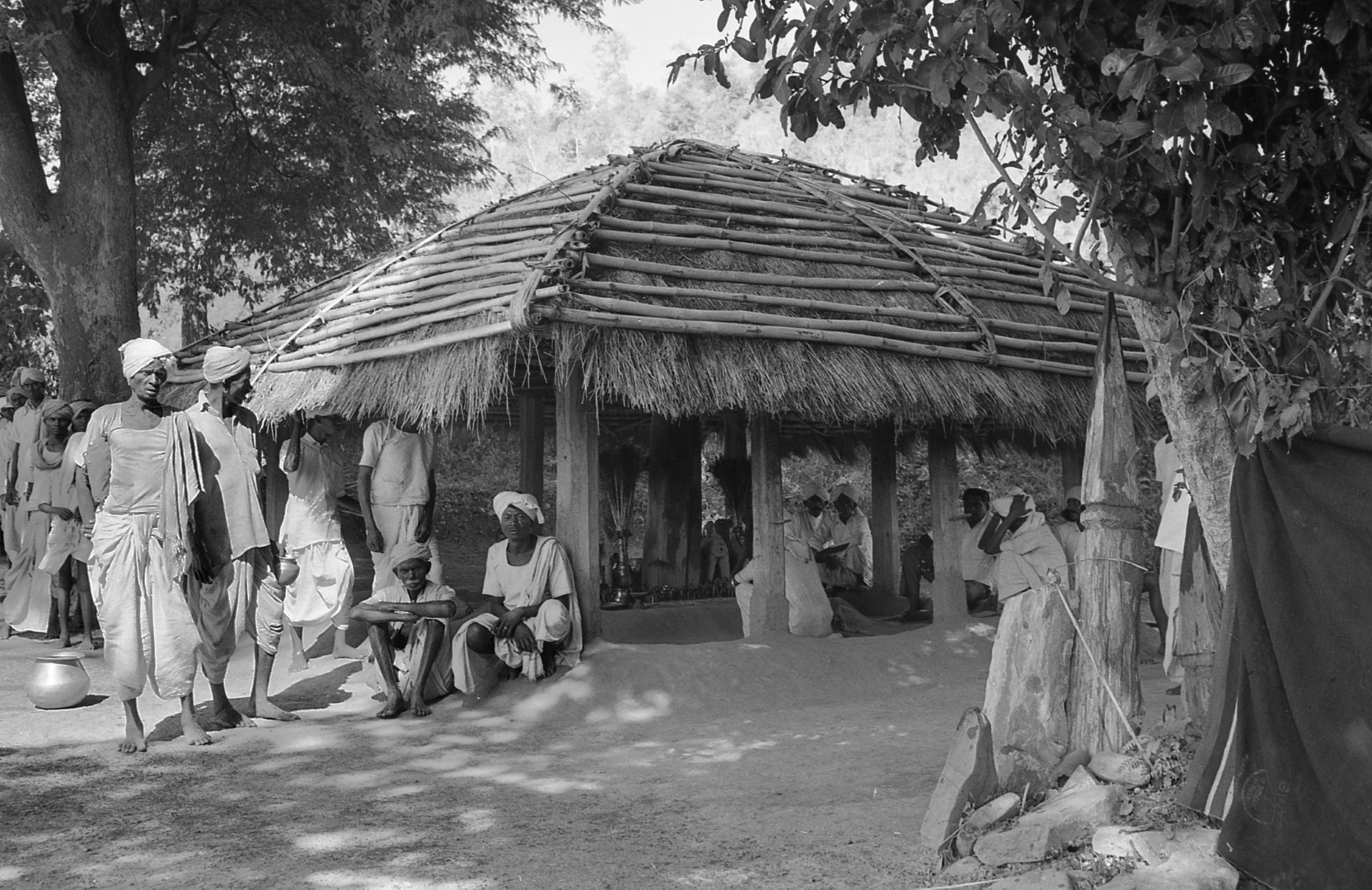

Awal shrine

This is a Raj Gond festival to the vilage mother deity.

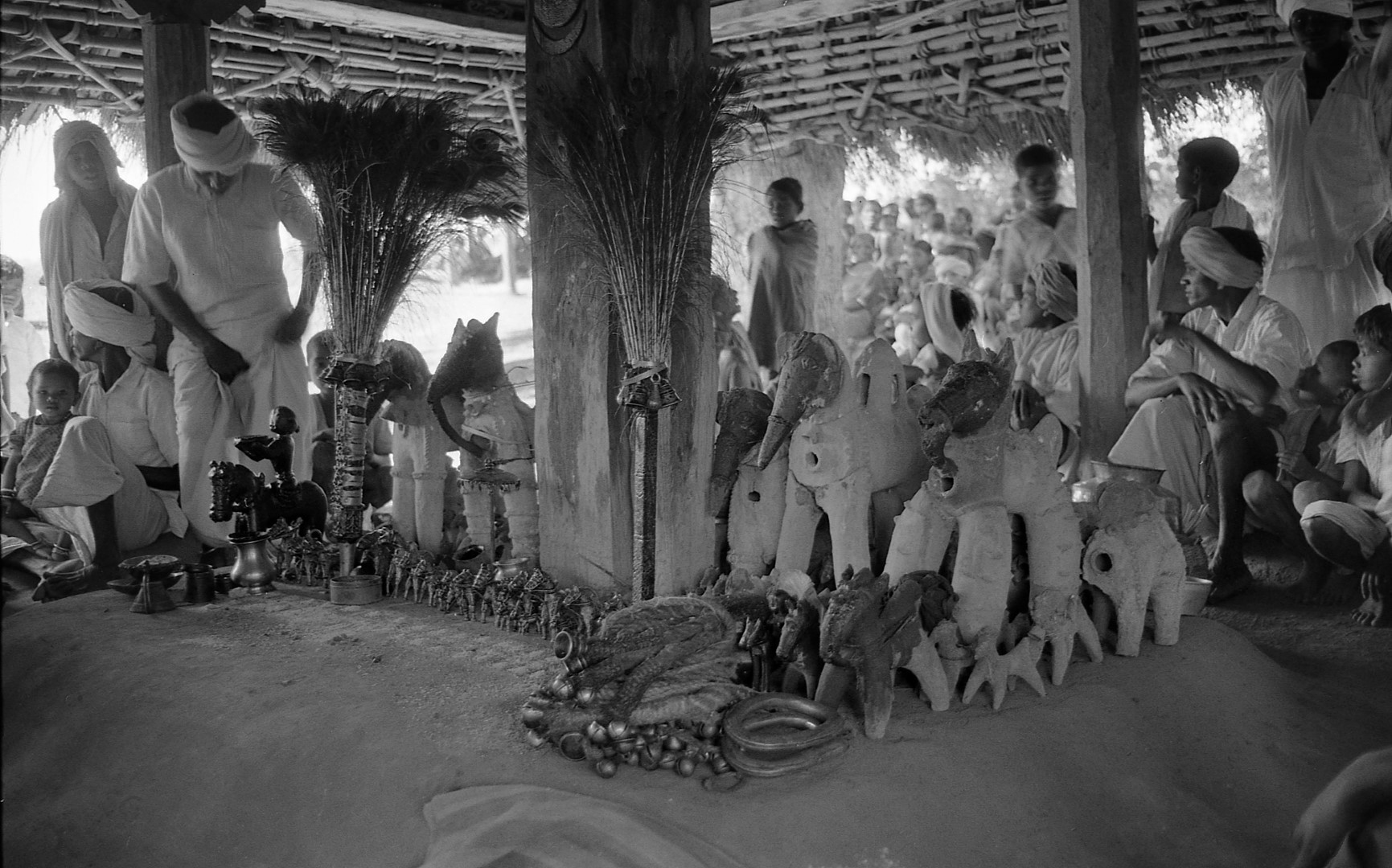

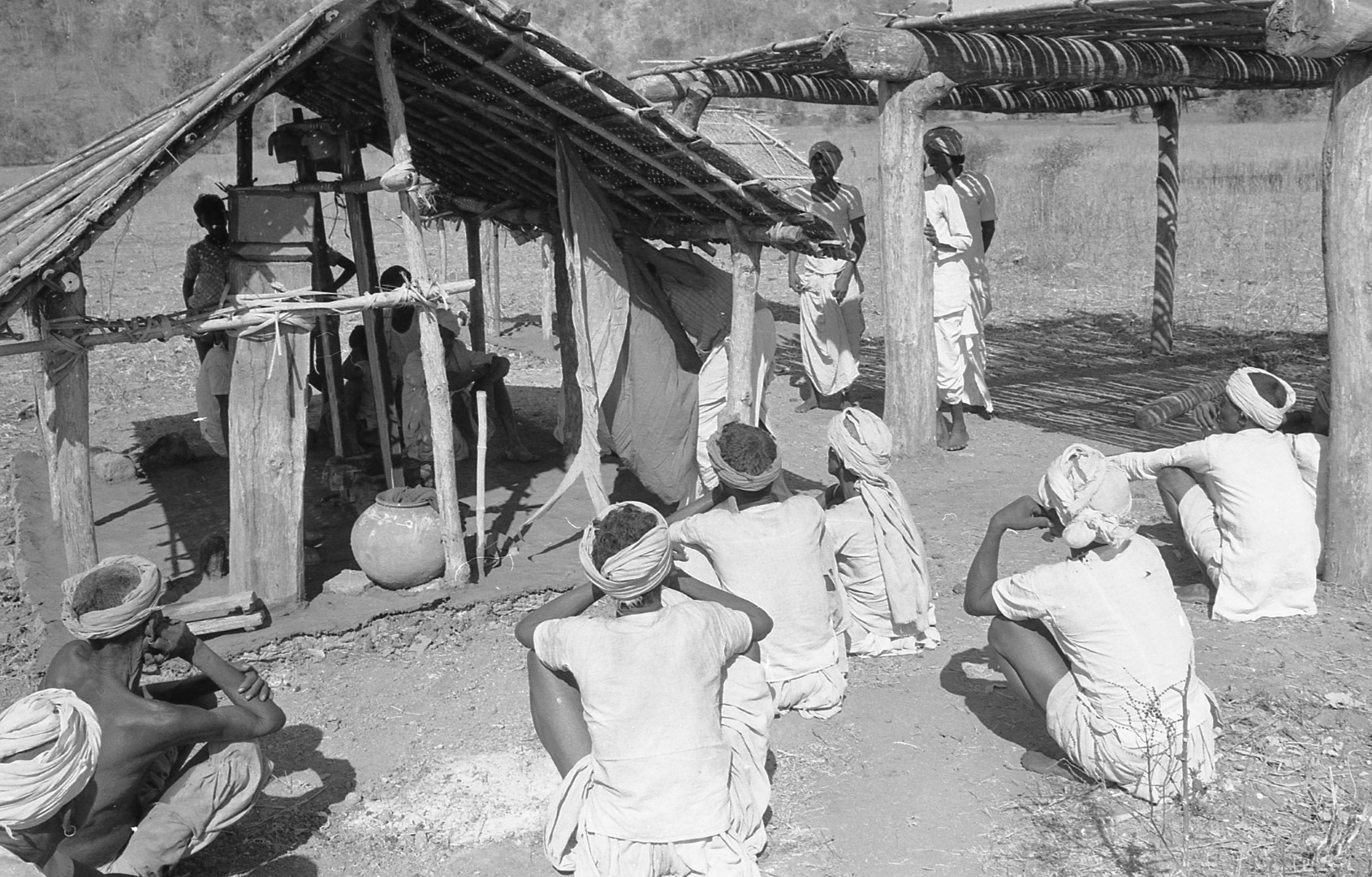

Bhimalik, the Kolam deity in Sungapur

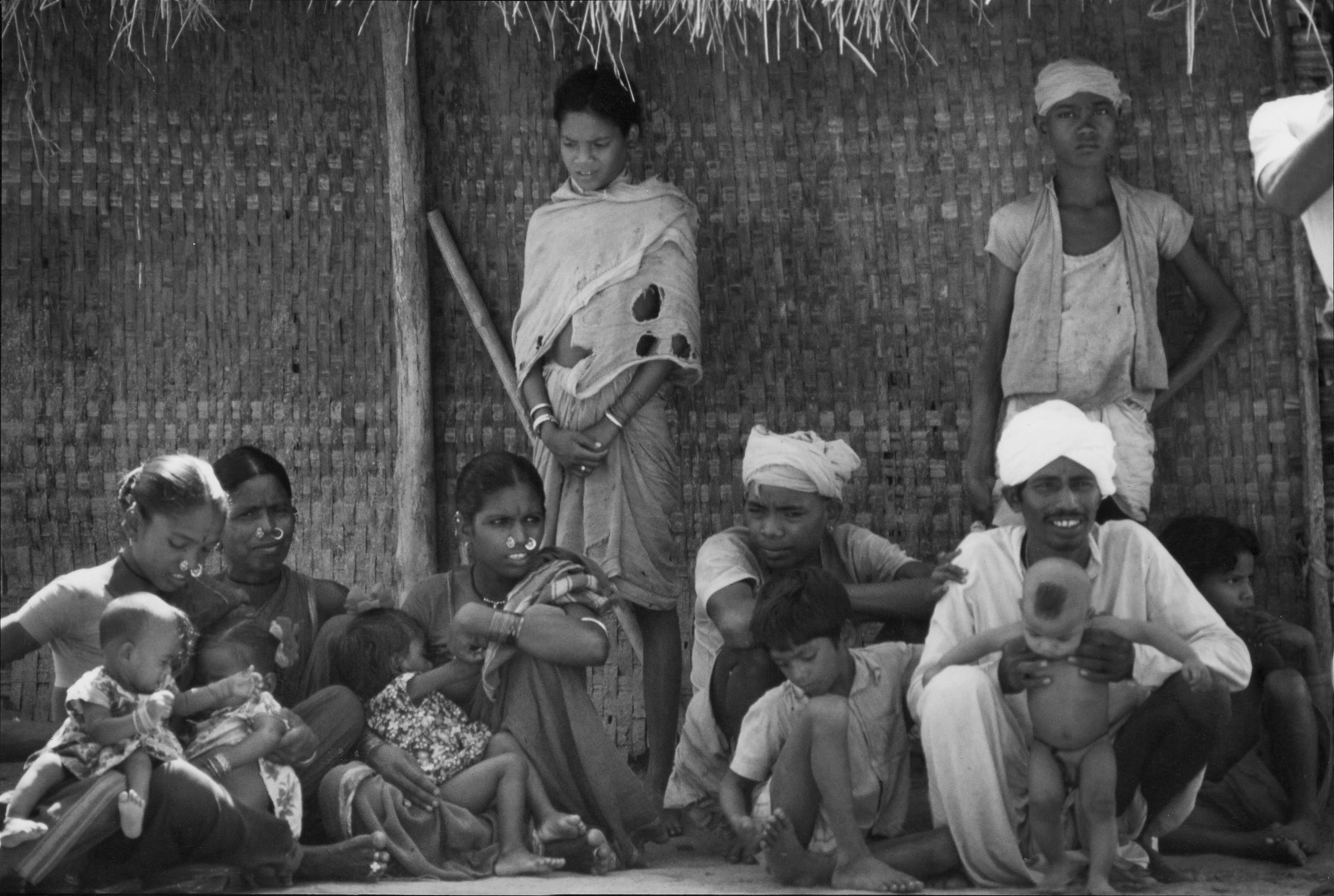

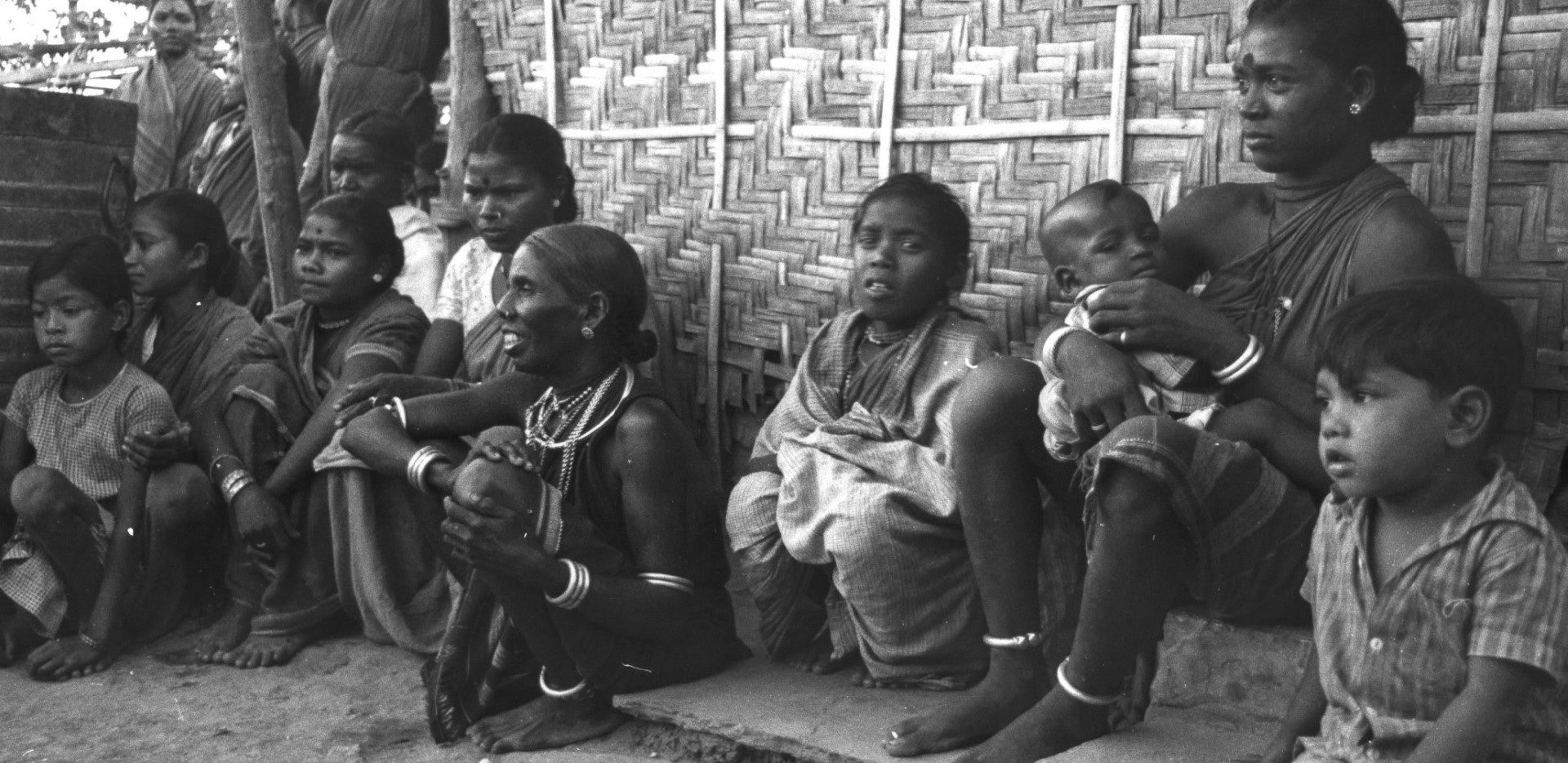

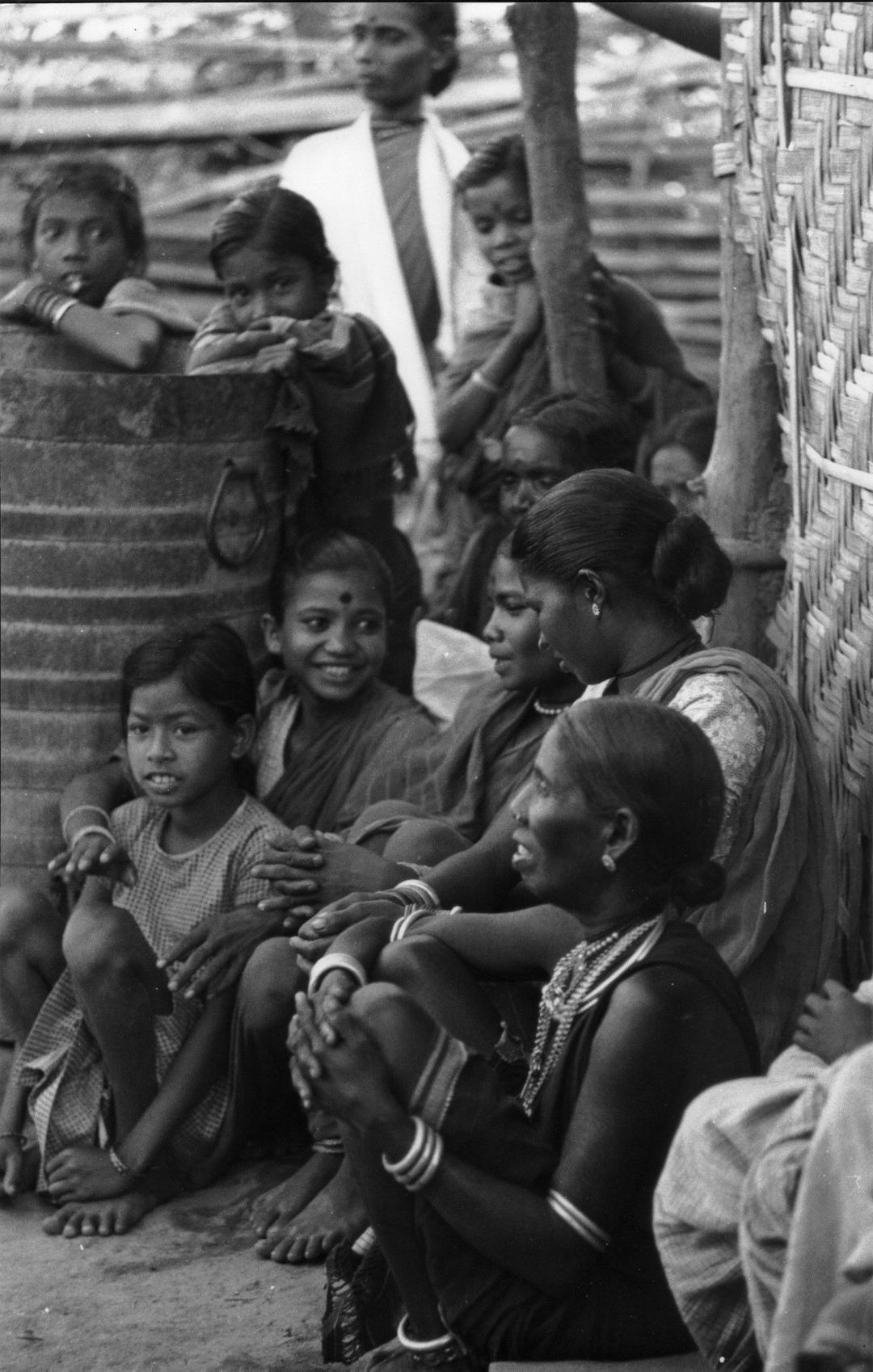

Bhimalk is the major deity of the Kolam tribe. The Kolam people live in the same area as the Raj Gond, but in separate villages. One of the most famous Kolam villages in the Asifabad area is Sungapur. It is only three miles from Ginnedhari. The Kolam and the Raj Gond people have a similar language, clan and phratry social structure. Although they do not intermarry, they cooperate in many ways. The Raj Gonds actively worship at the Kolam shrines and the Kolam participate in many Raj Gond festivals, in particular the Raj Gond Dandari festivities. Many Raj Gonds consider Bhimalik to be an important and powerful deity and plead to it for special favours and to cure many maladies. They always attend the important festivals to Bhimalik.

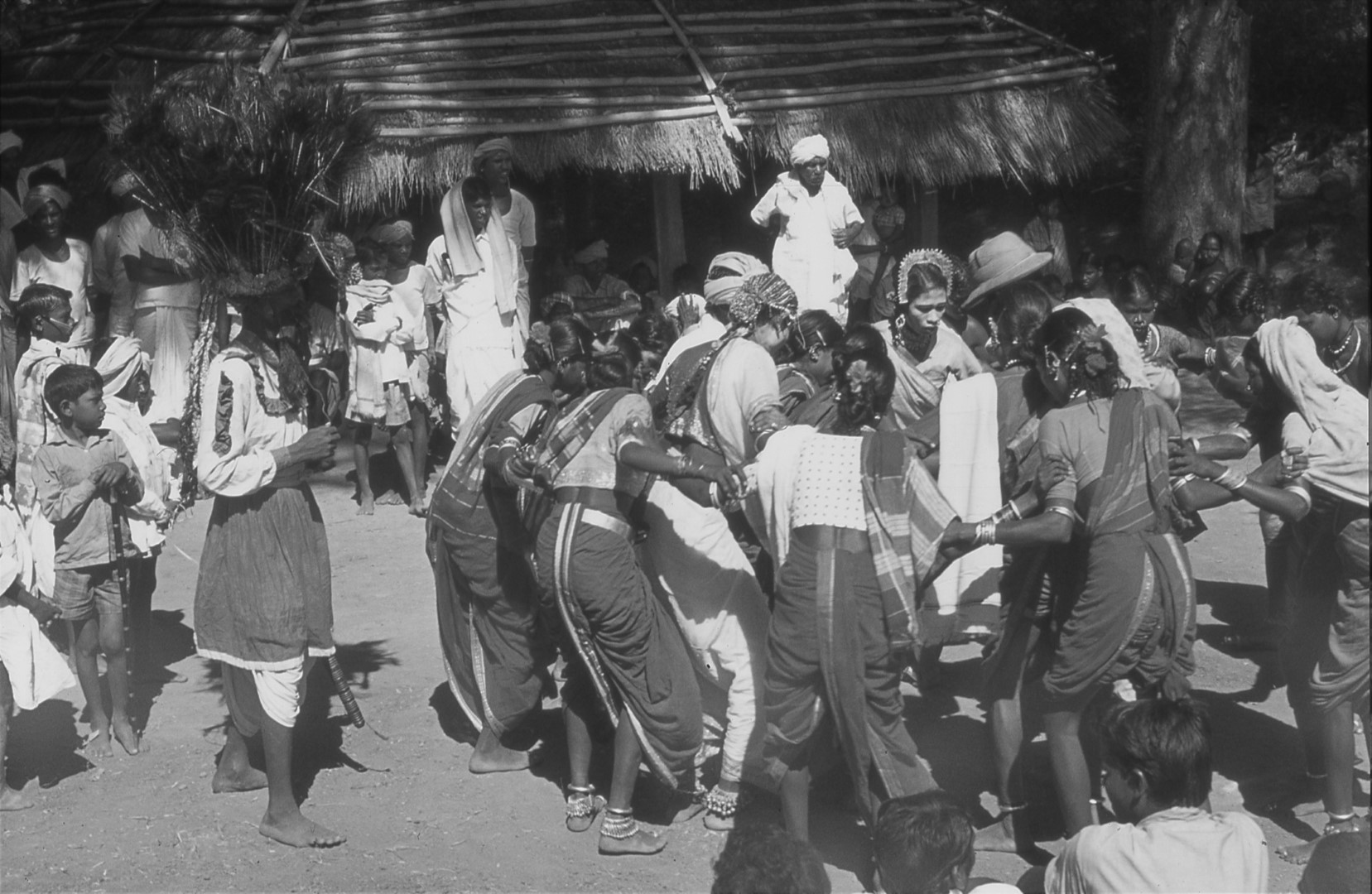

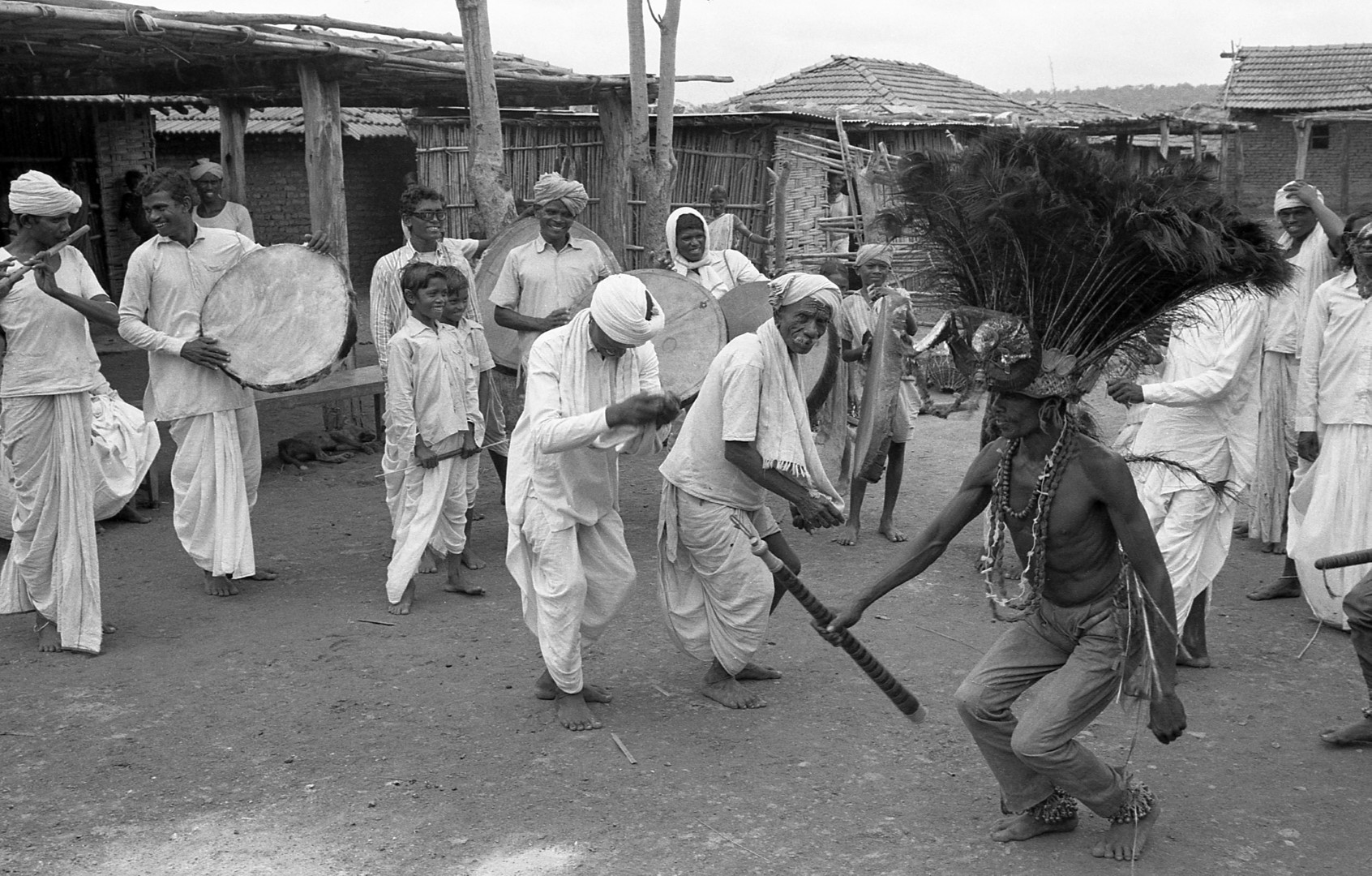

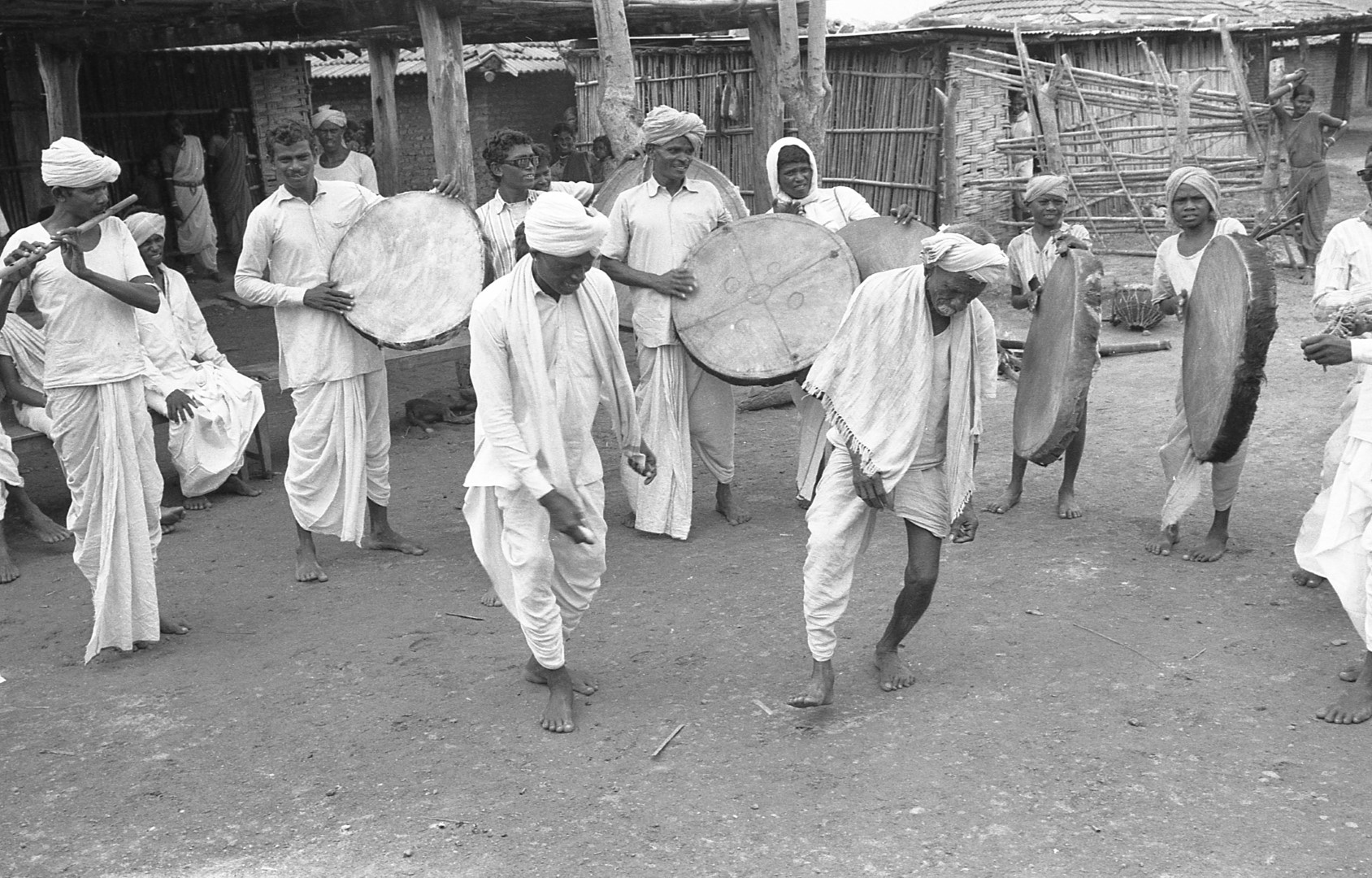

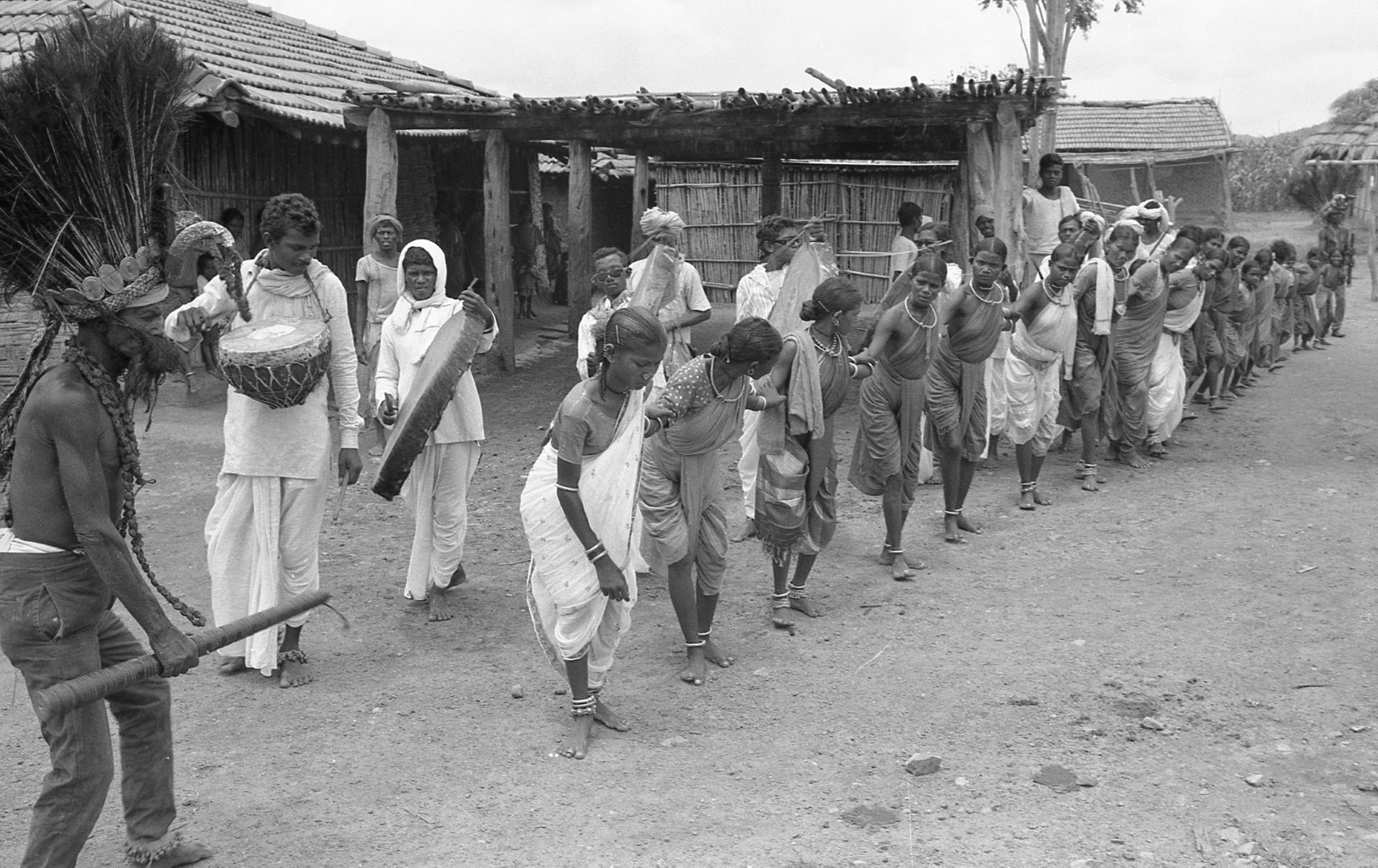

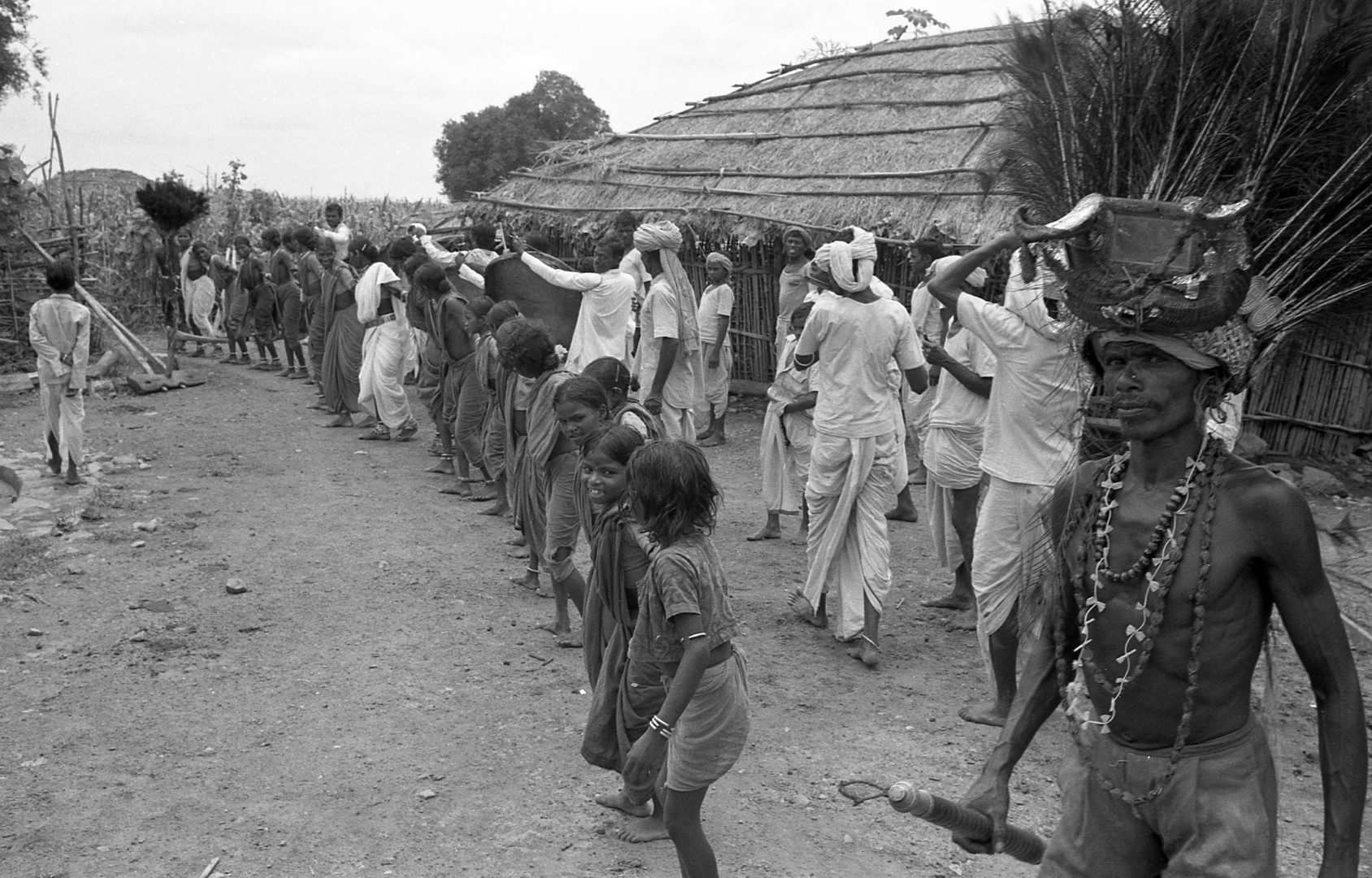

DANDARI FESTIVAL

Today this great festival has become the most important event in Raj Gond cultural year. Since my film, ‘Reflections in a Peacock Crown’, made for the BBC in 1981 (which is available on this website) many similar films have been made. Every year a troupe of Dandari dancers perform at India’s Independence Day celebrations in Delhi. However today it has been adapted into a Bollywood spectacle and a tourist attraction.

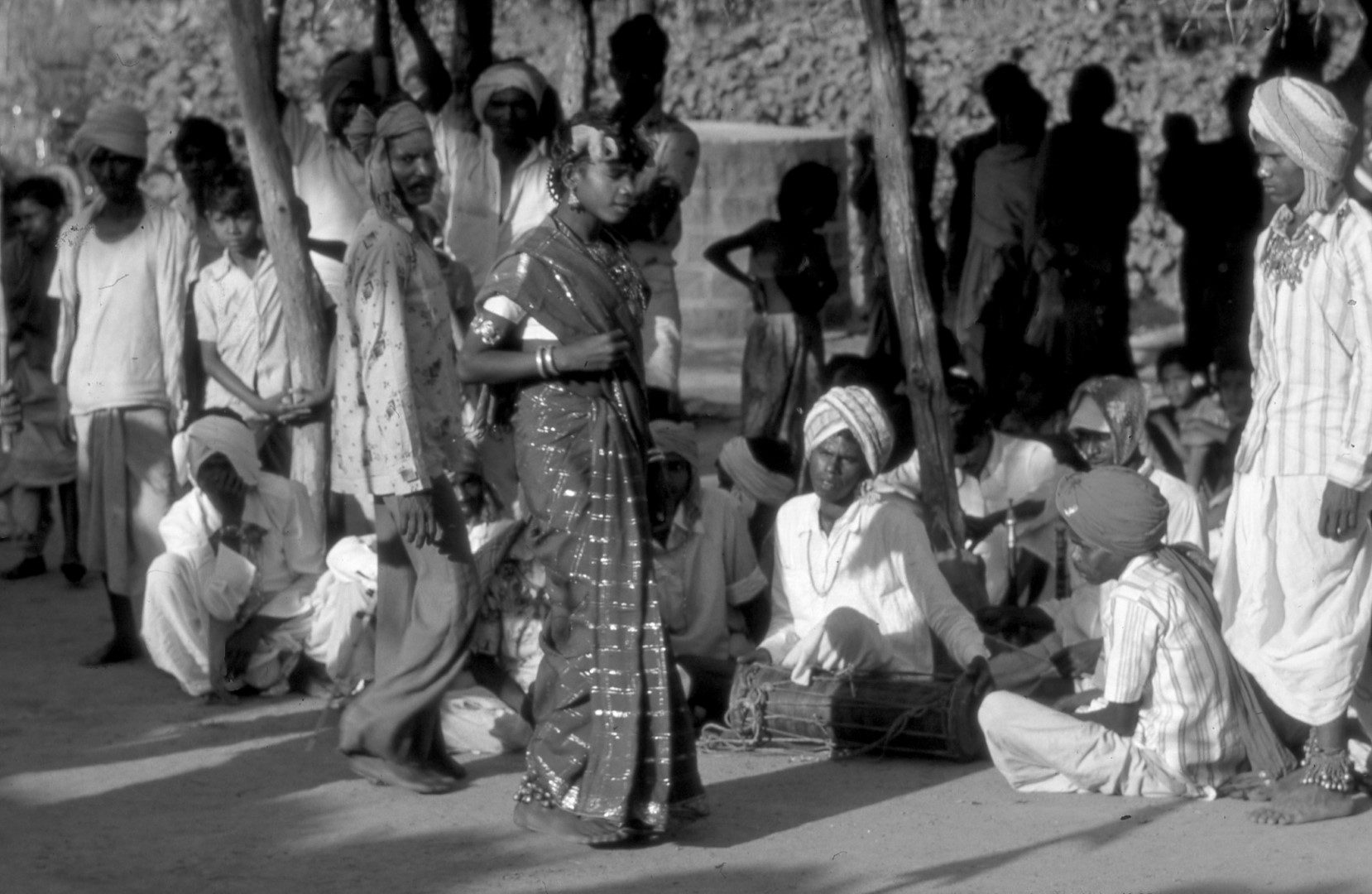

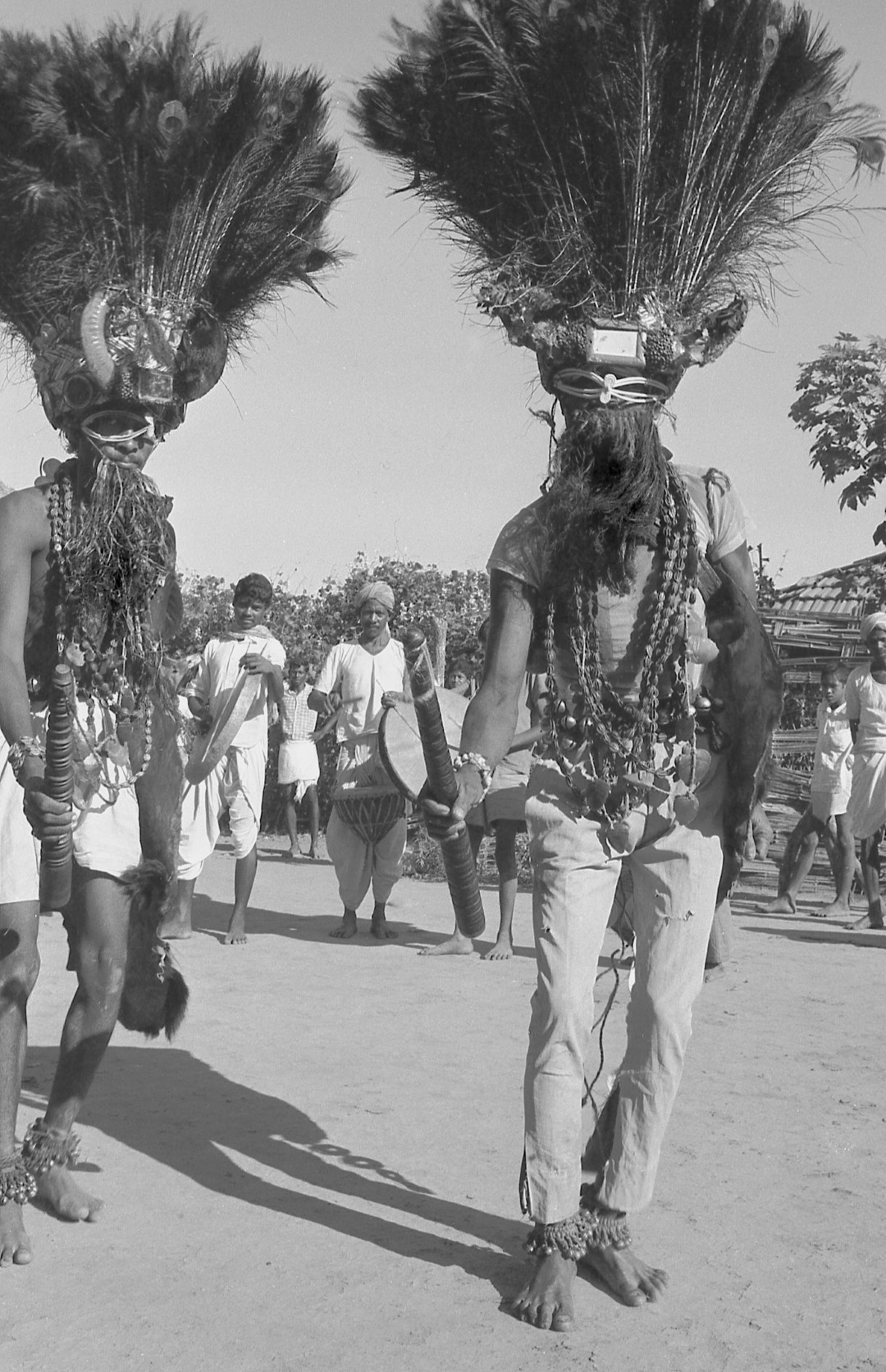

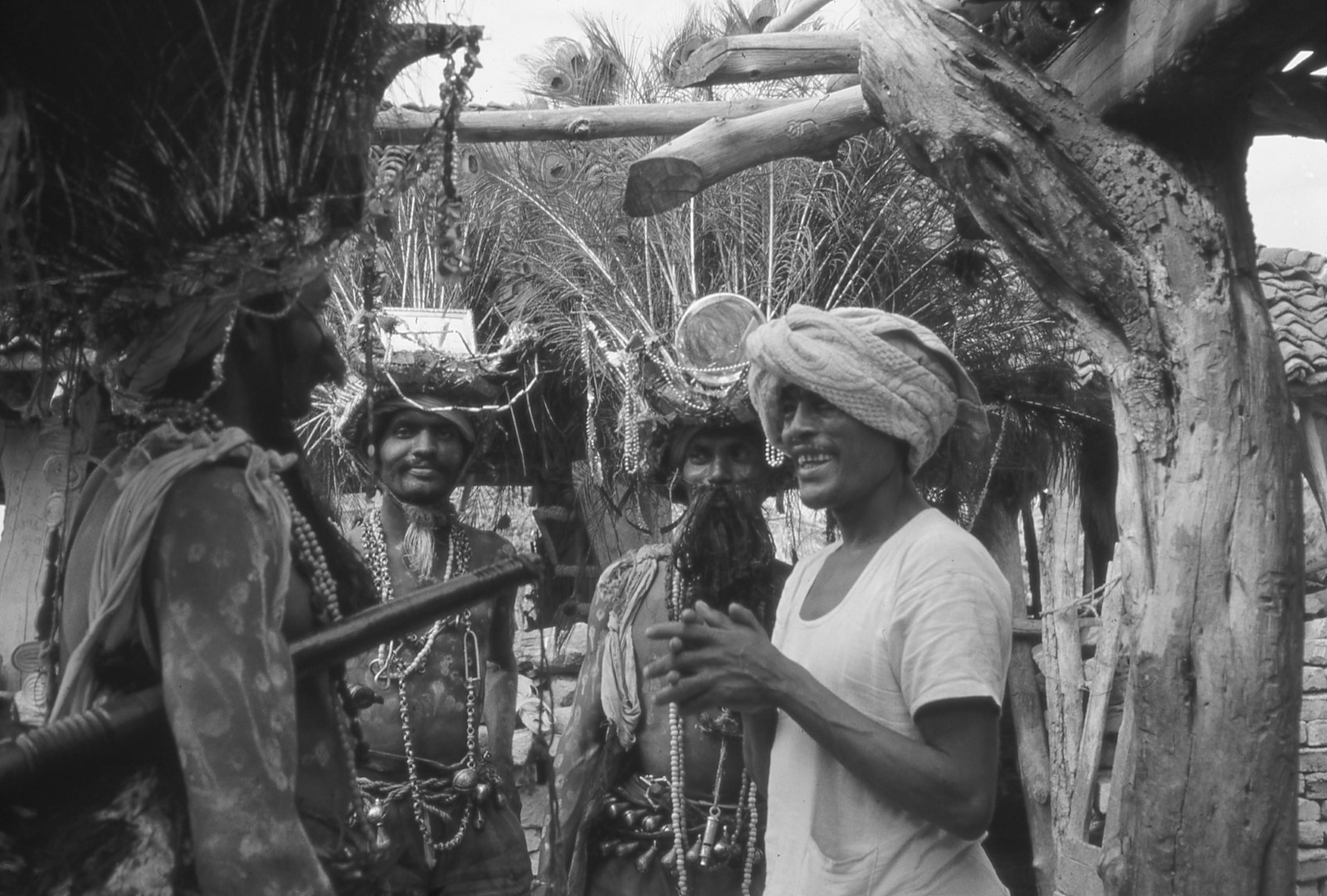

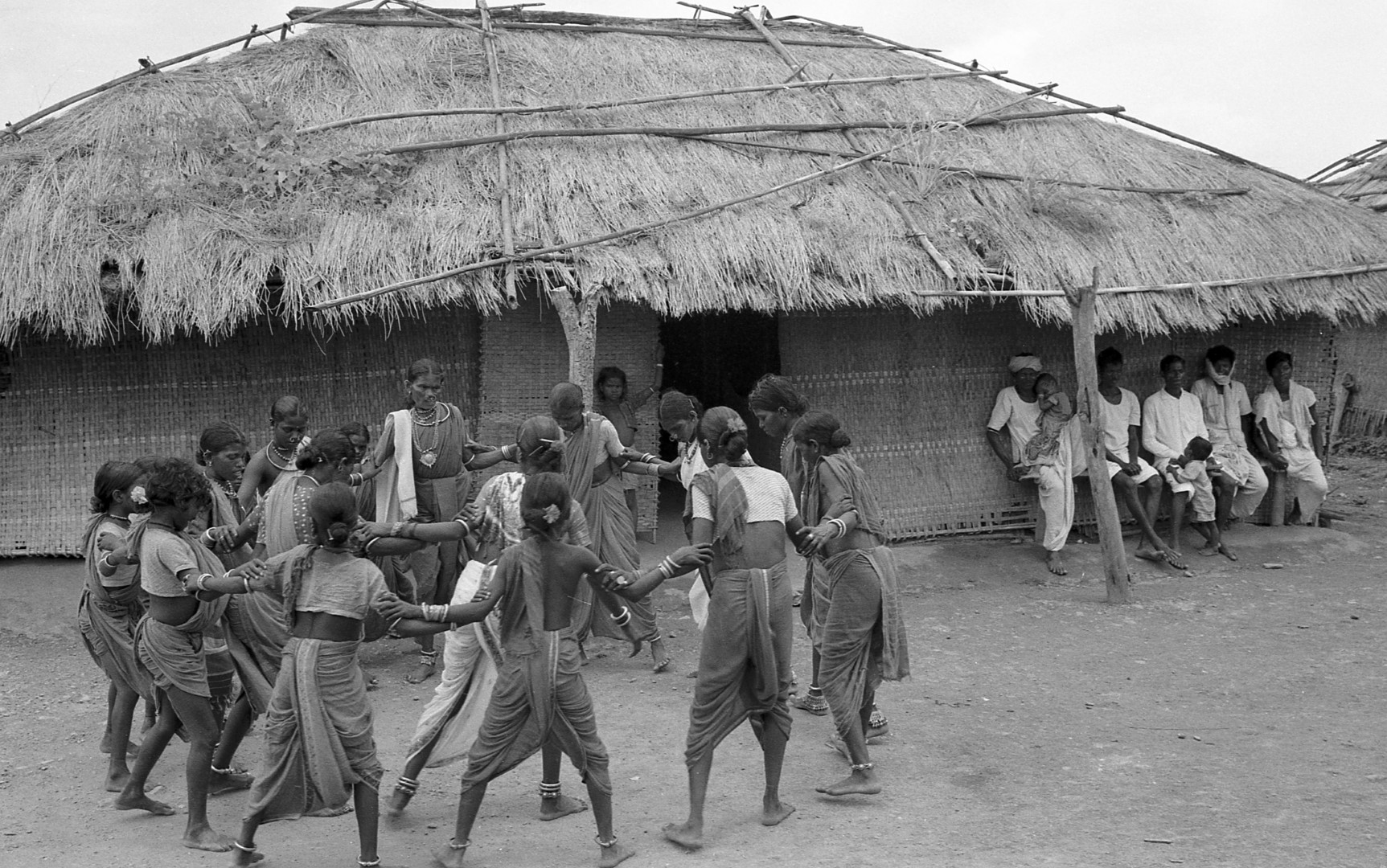

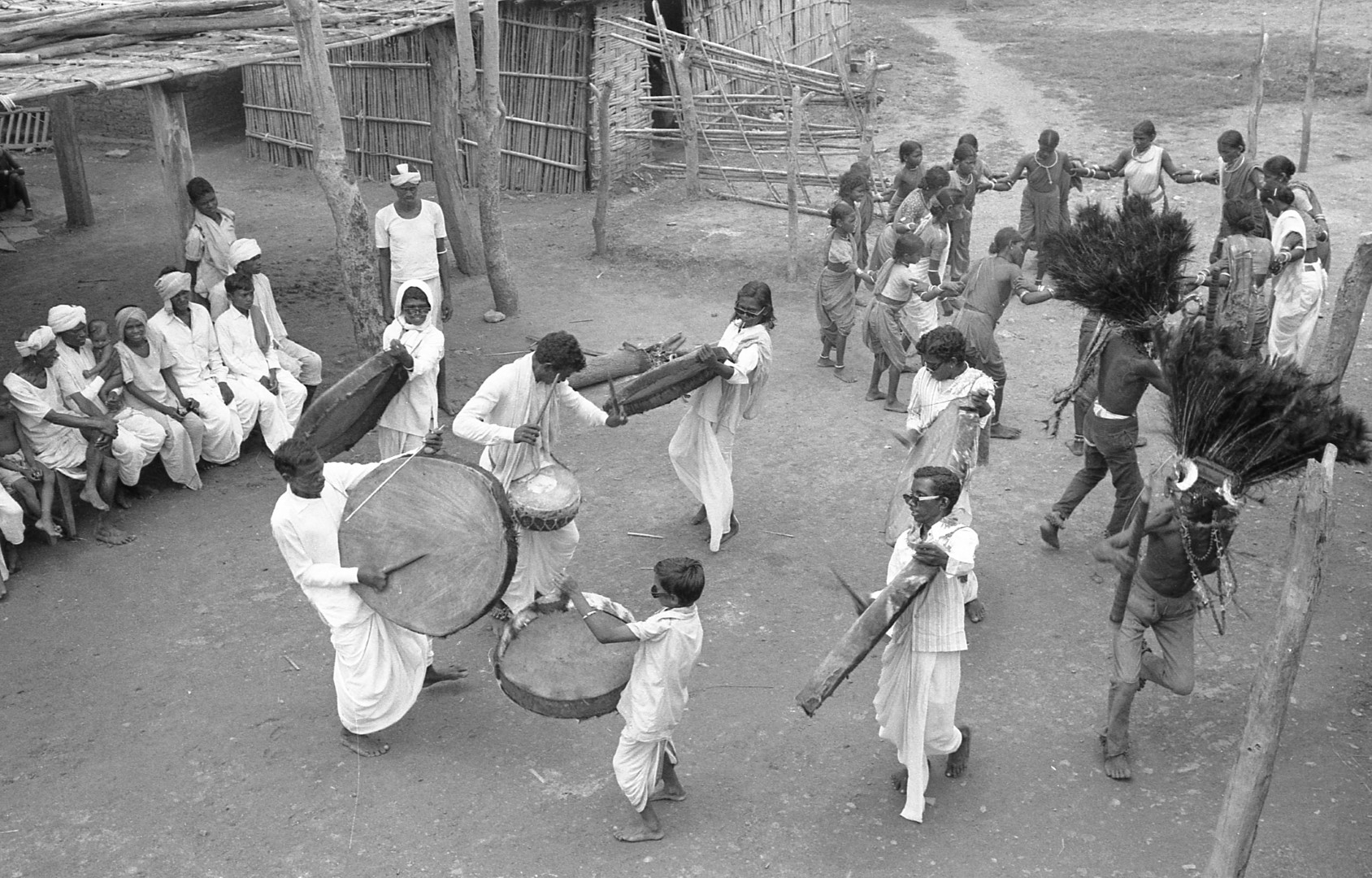

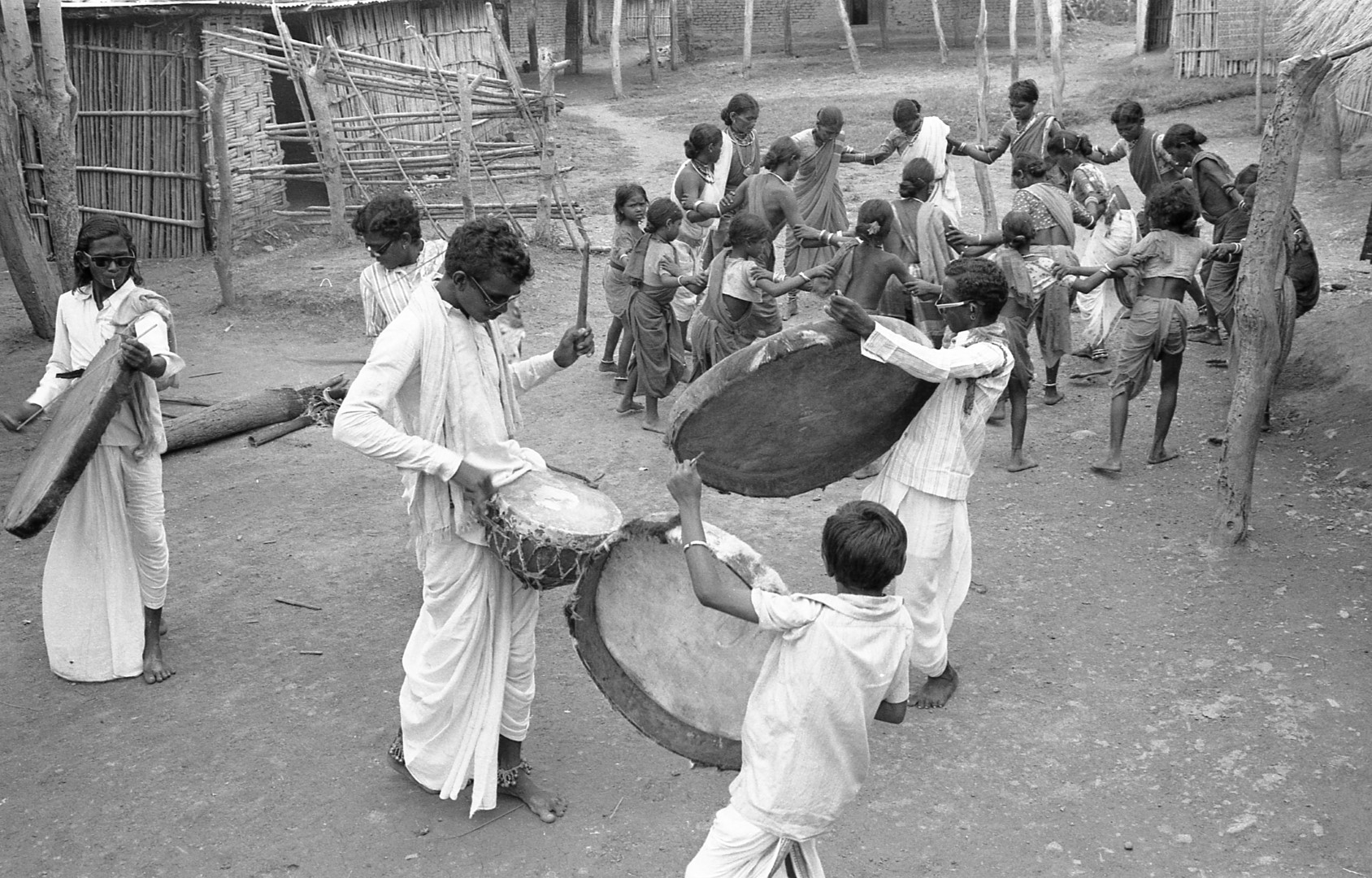

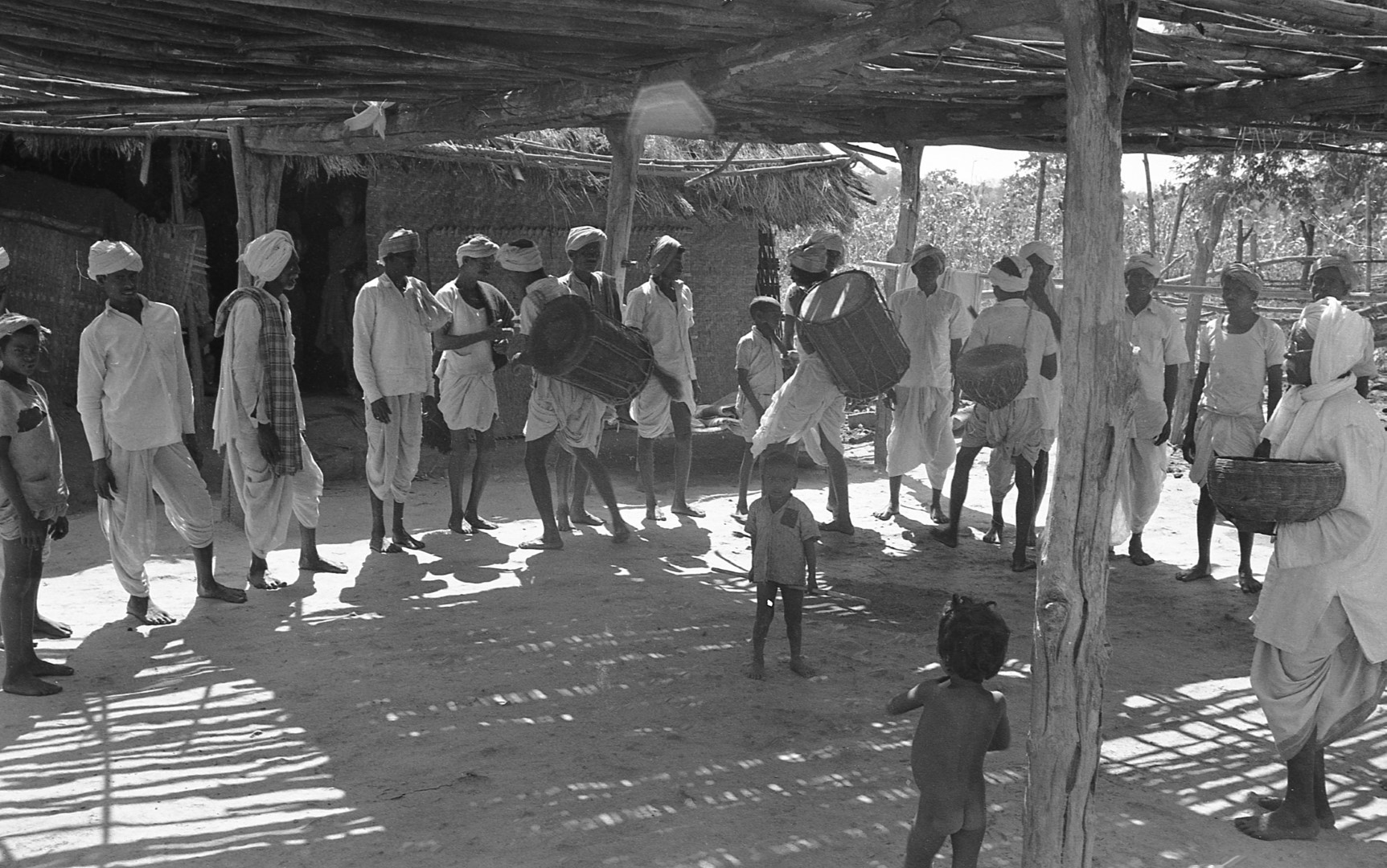

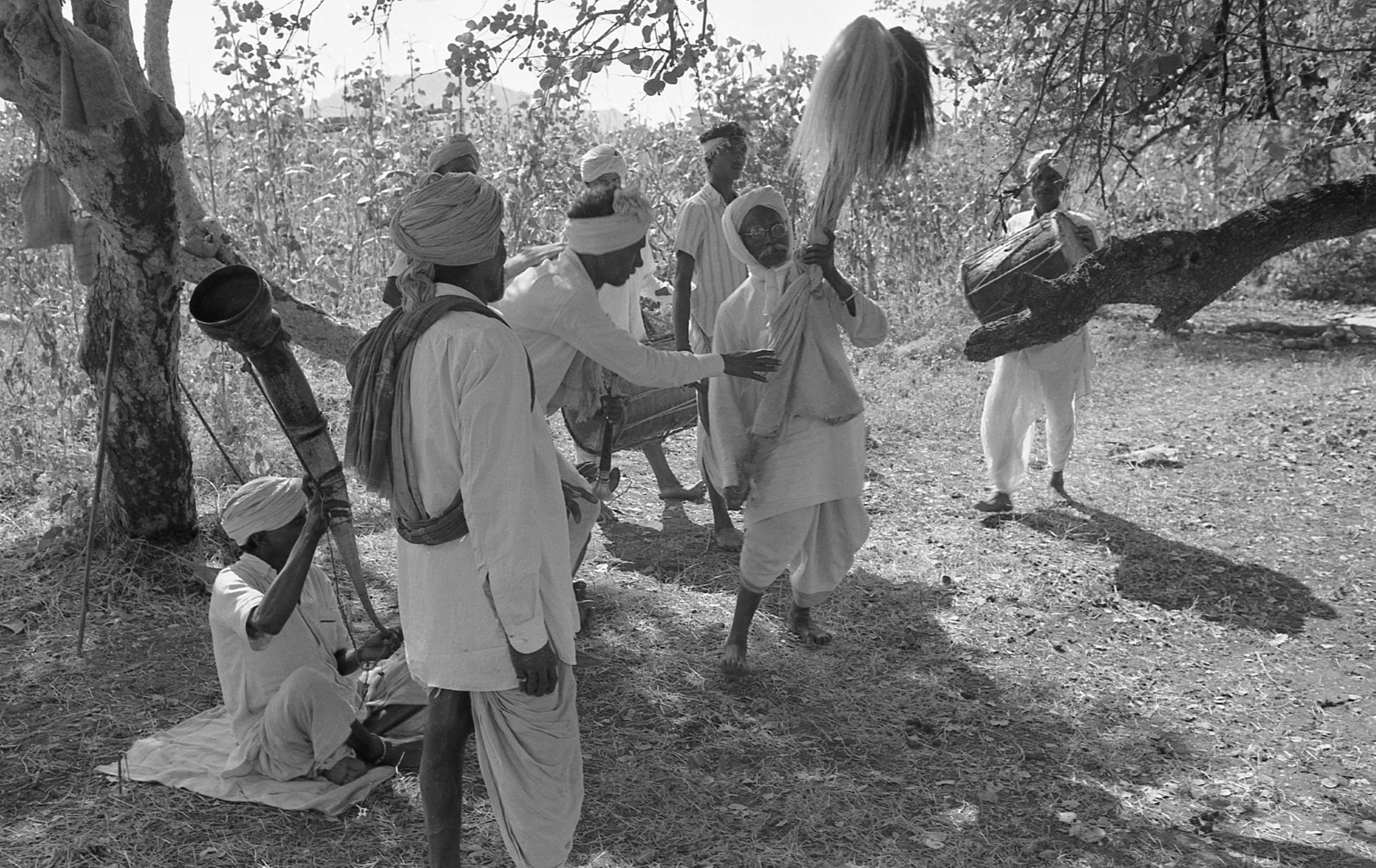

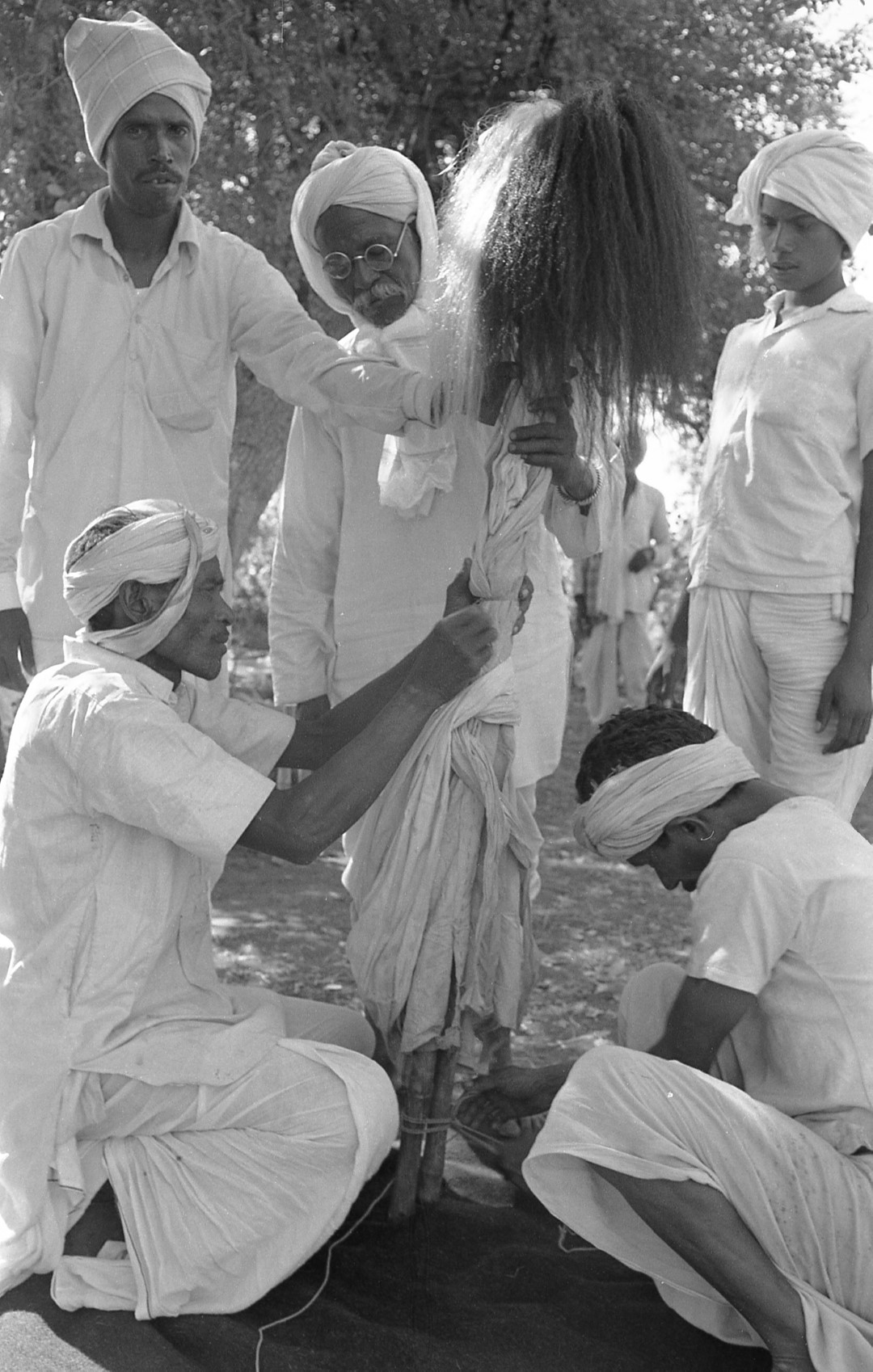

Originally it was a week-long festival in the cool season of February. Troupes of peacock crowned divine jesters, ‘gusark’, Lords of Misrule, visited neighbouring villages with musicians and elders accompanying boys dressed as young brides called ‘purik’, meaning young chicks.

The purik represent ‘Yetmasur’, the daughters of ‘Nataranjan Guru’, the God of Creation. The mythical Gond ancestor, ‘Pahandi Kupar Lingal‘, brought the ‘purik‘ back from the god’s cave to be his wives and they gave birth to the ‘Koitur’, the Raj Gond people. The ‘purik’ are accompanied by ‘mauk’, meaning sambar deer, to look after them.

Daily behaviour, that is normally carefully ordered and inhibited, is challenged by the jesters, the ‘gusark’, who dance, talk in exaggeratedly absurd language and crack raunchy jokes. ‘Dandari‘ is a bacchanalia – a libertarian festival.

This festival, full of laughter and absurdity, reminds people that before the world was created it was an ocean of chaos that was put into order by the gods and by ‘Shiva Nataranjan Guru‘, who gave order and form to Raj Gond culture and society. It is at the heart of ‘Koitur’ philosophy and way of life. It gives meaning and structure to their life and the world in which they live.

Just as ‘Dandari’ celebrates the bringing of young brides from the land of the gods, so dance parties visit other villages where their daughters have become wives and from which they have taken brides themselves. It is a festival full of humour and also a forum in which future kinship ties and marriages are arranged. This is the core of the Raj Gond’s kinship system and family politics.

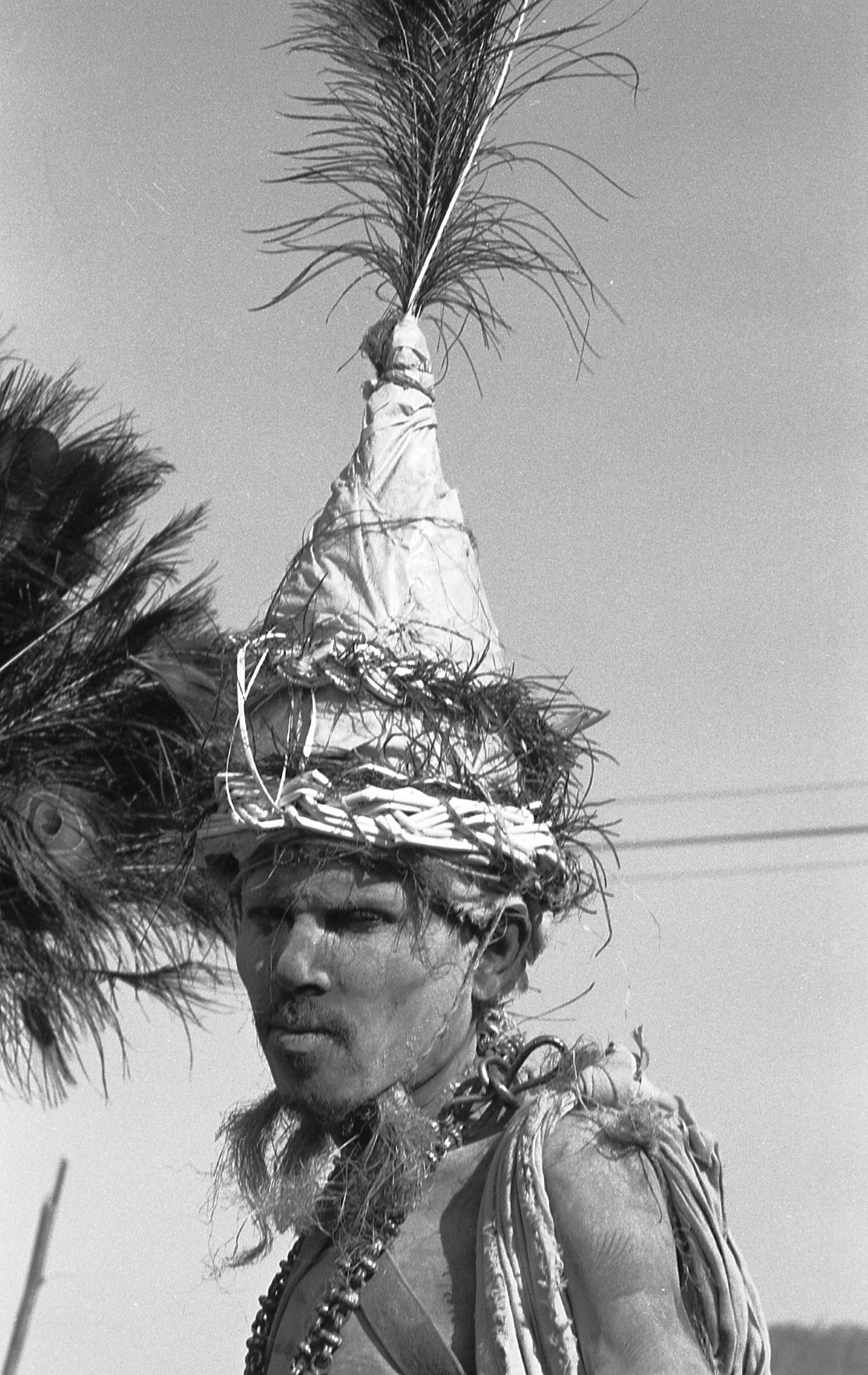

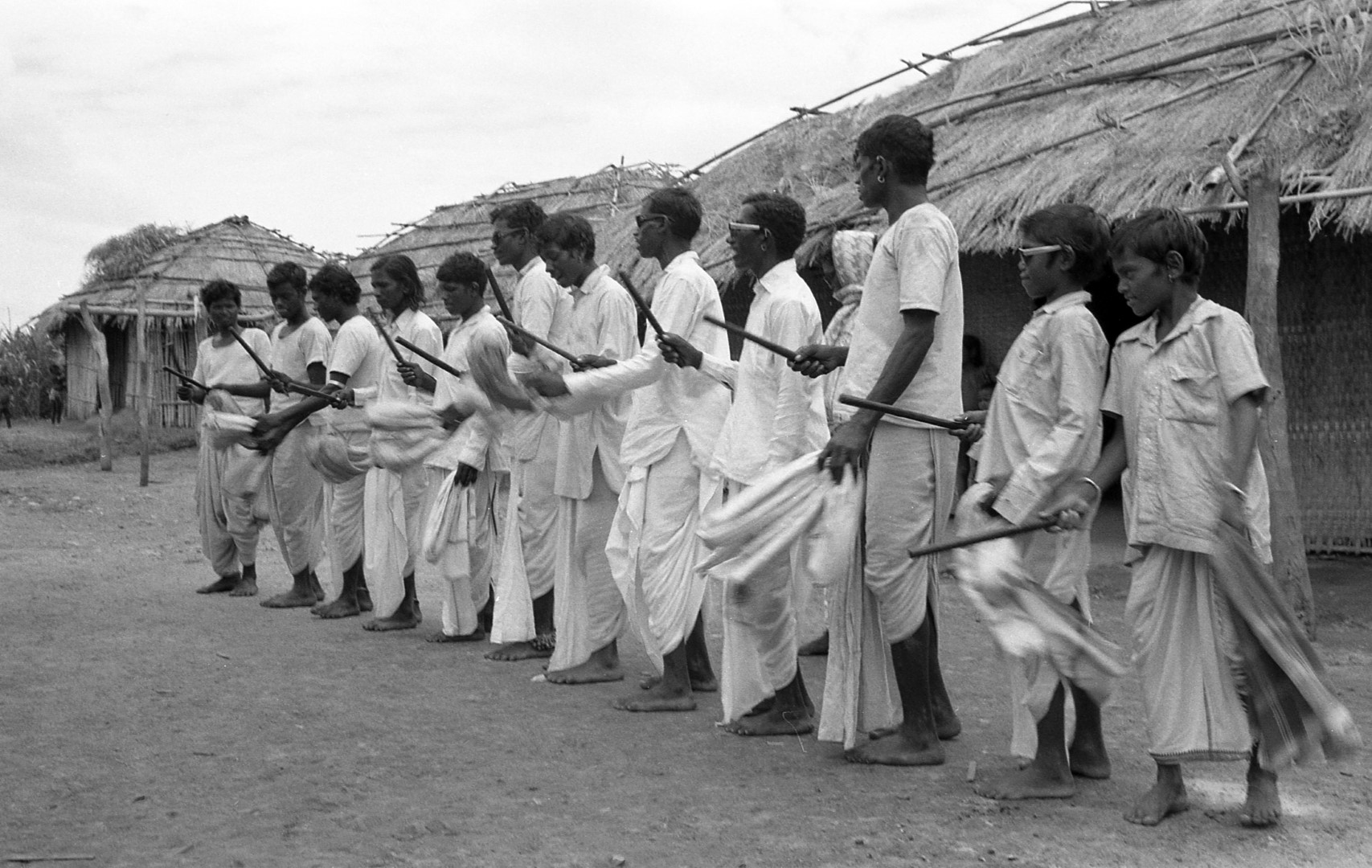

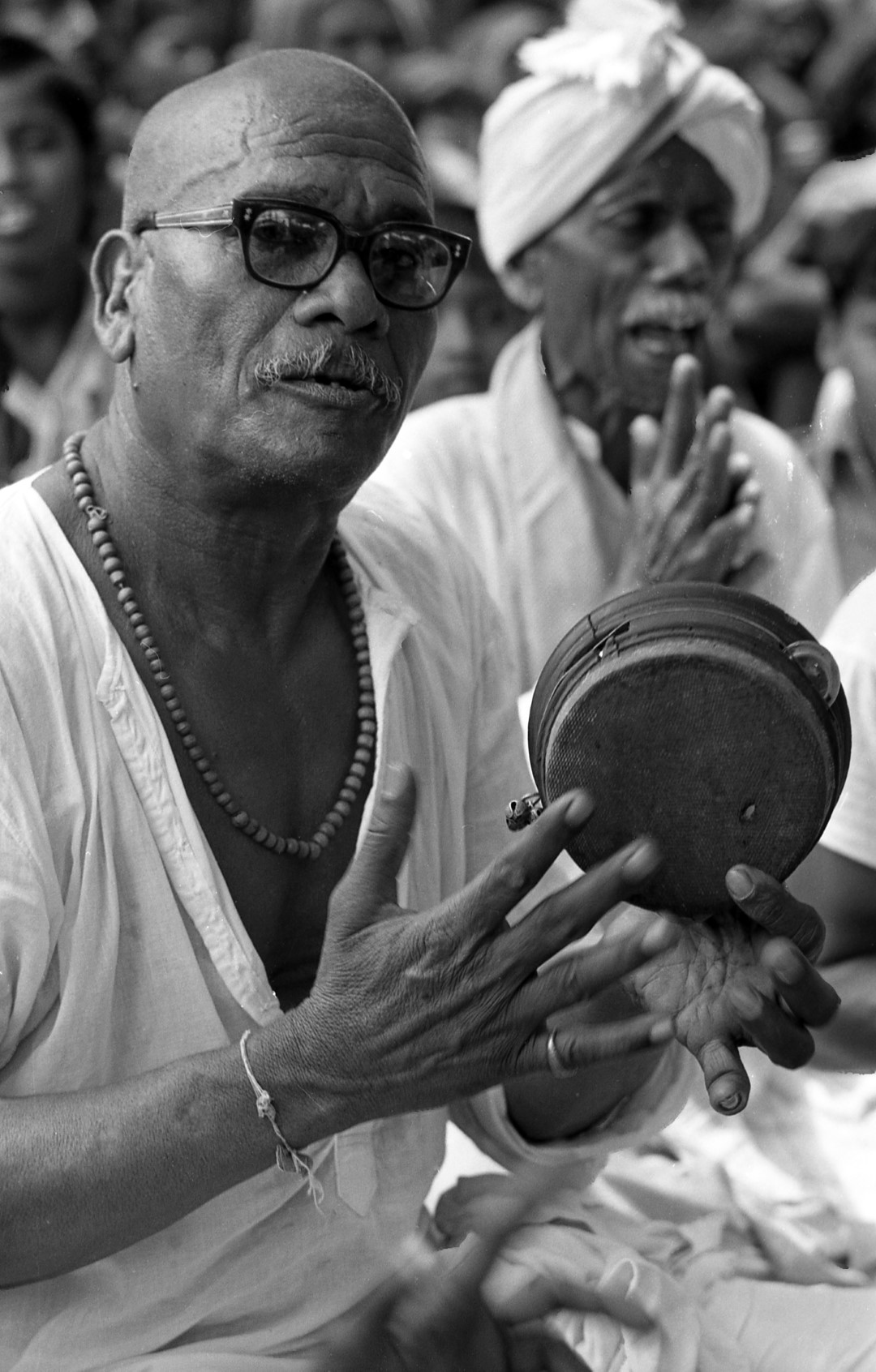

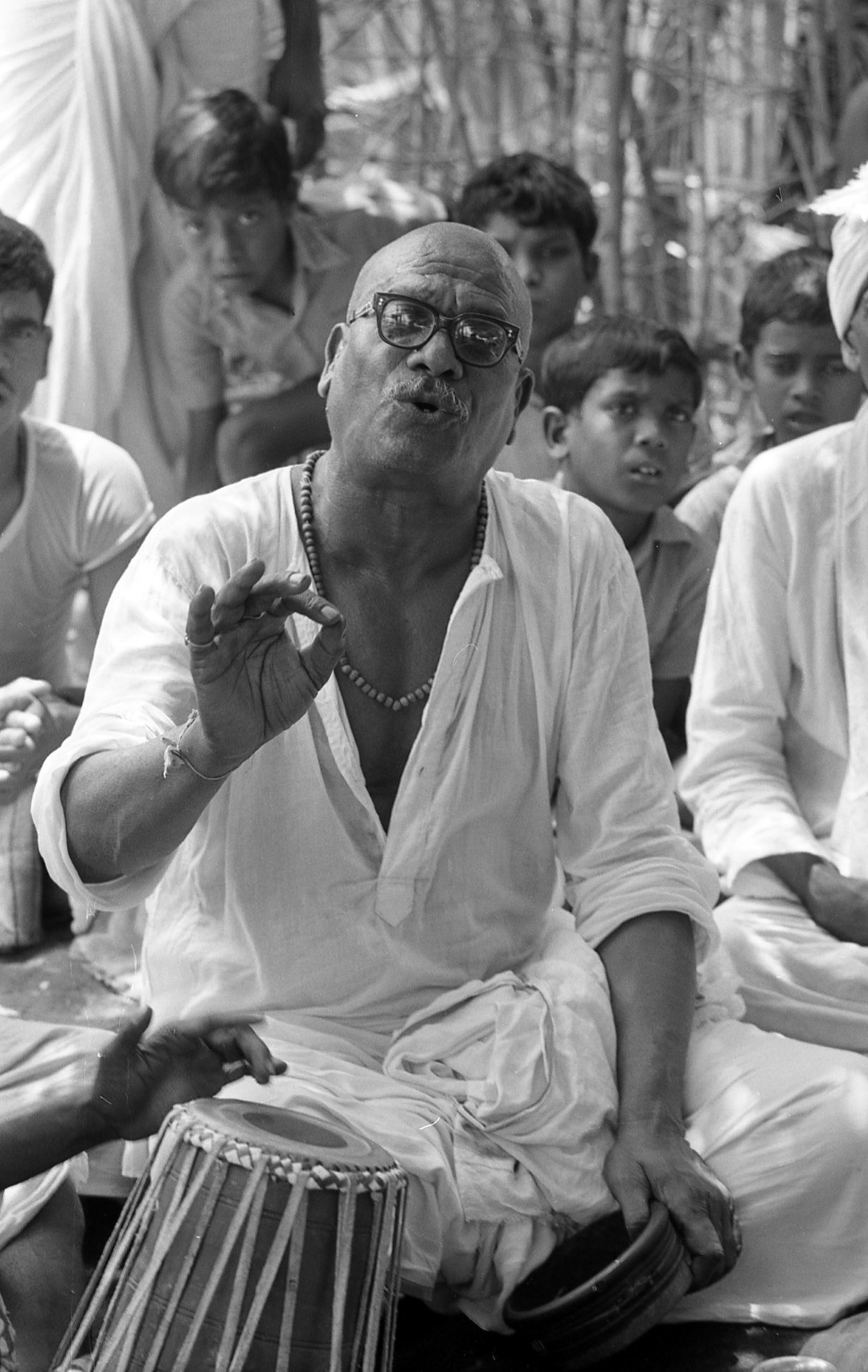

When the peacock feather crowns have been repaired and consecrated a team of married men are selected from each village to be the ‘Gursark‘, jesters, for the next days of the festival. They bathe and purify themselves. Then they smear themselves in a paste of ashes and flour symbolising that they have become like ‘Shiva Natarajan Guru‘, whose dancing maintains order in the universe. They now represent wise sages, who understand the nature of reality. They have divested themselves of their everyday personality, which has been transferred into their ‘sota‘, the carved baton that each of them carries. They are now divine god-like beings and their batons are their everyday selves. Hanging behind them is a leather skin symbolising the mediation mat of ‘Shiva Natarajan Guru‘, the mat on which he attained enlightenment, wisdom and knowledge. Around his neck are necklaces of ‘rudraksh‘ beads denoting his sagacity. The spectacles that they wear imply that they are all-seeing. The ‘gusark’ are adorned with peacock feather crowns and conical hats. They wear mirrors to show people that they are mere reflections of normality. Their chaotic behaviour is the primordial state of nature. They are like the Hindu deity ‘Shiva‘, who meditated on the nature of human existence and became Hinduism’s great force of destruction and creation.

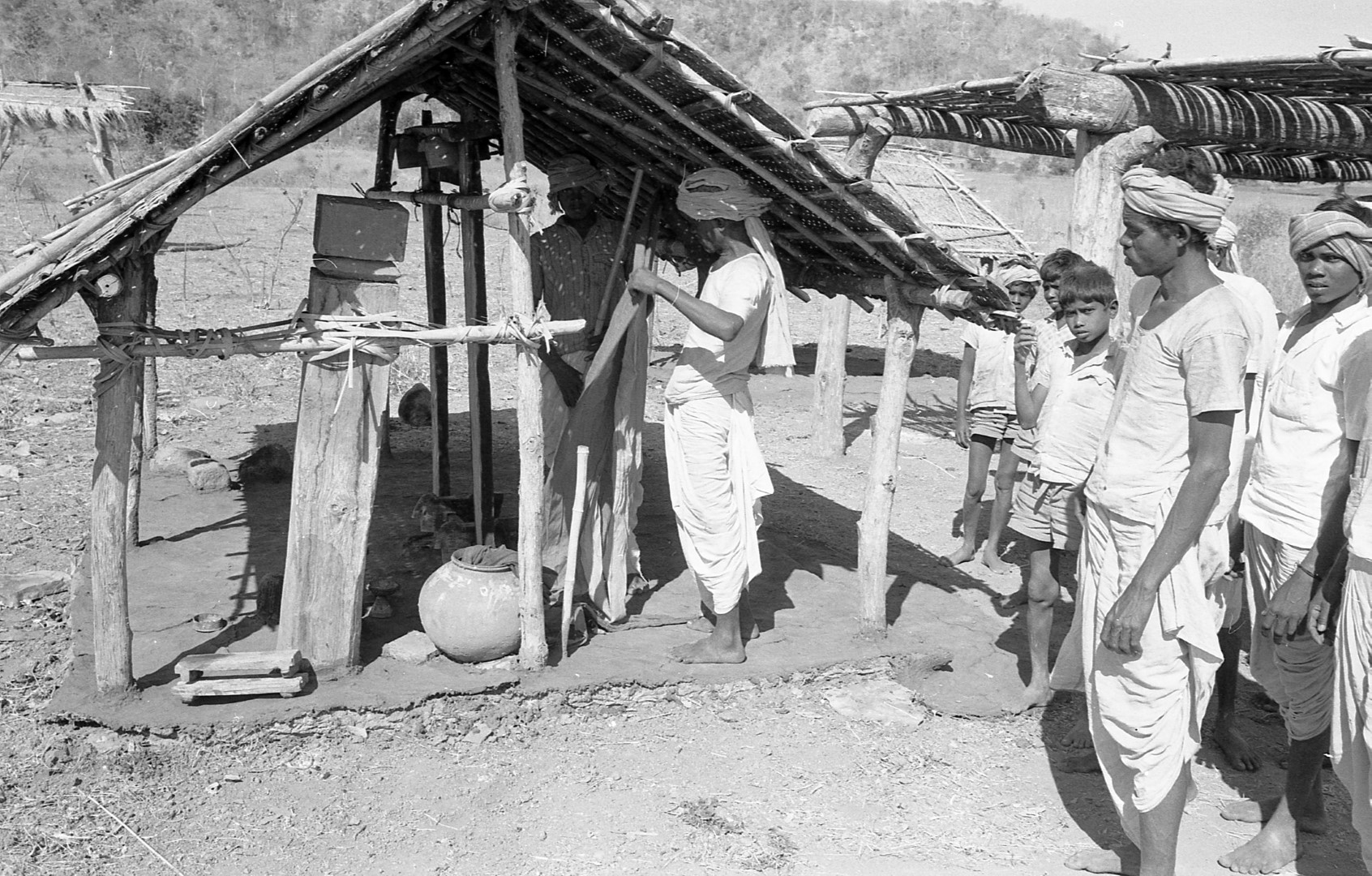

Dasserah (Beating the Village Boundary)

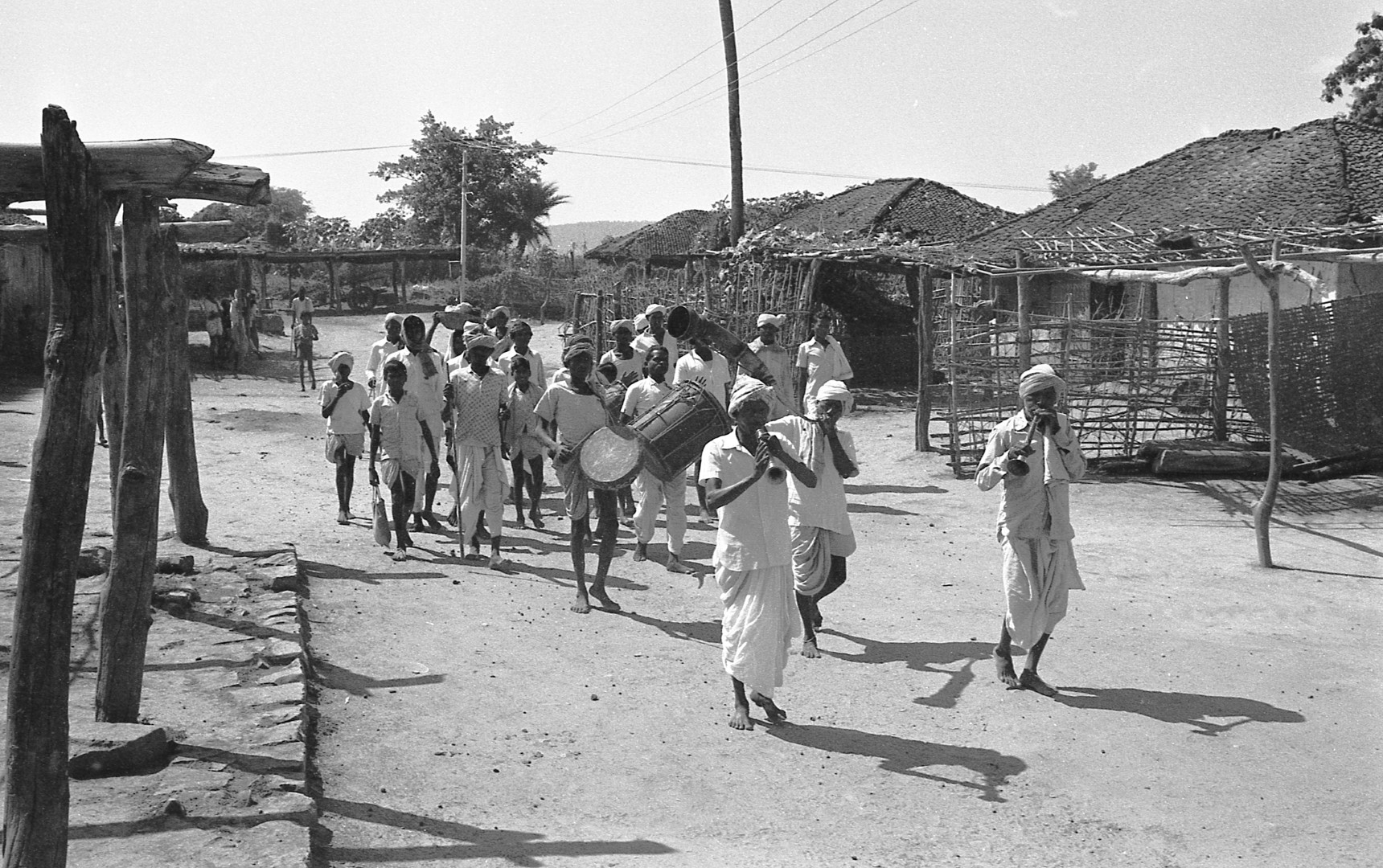

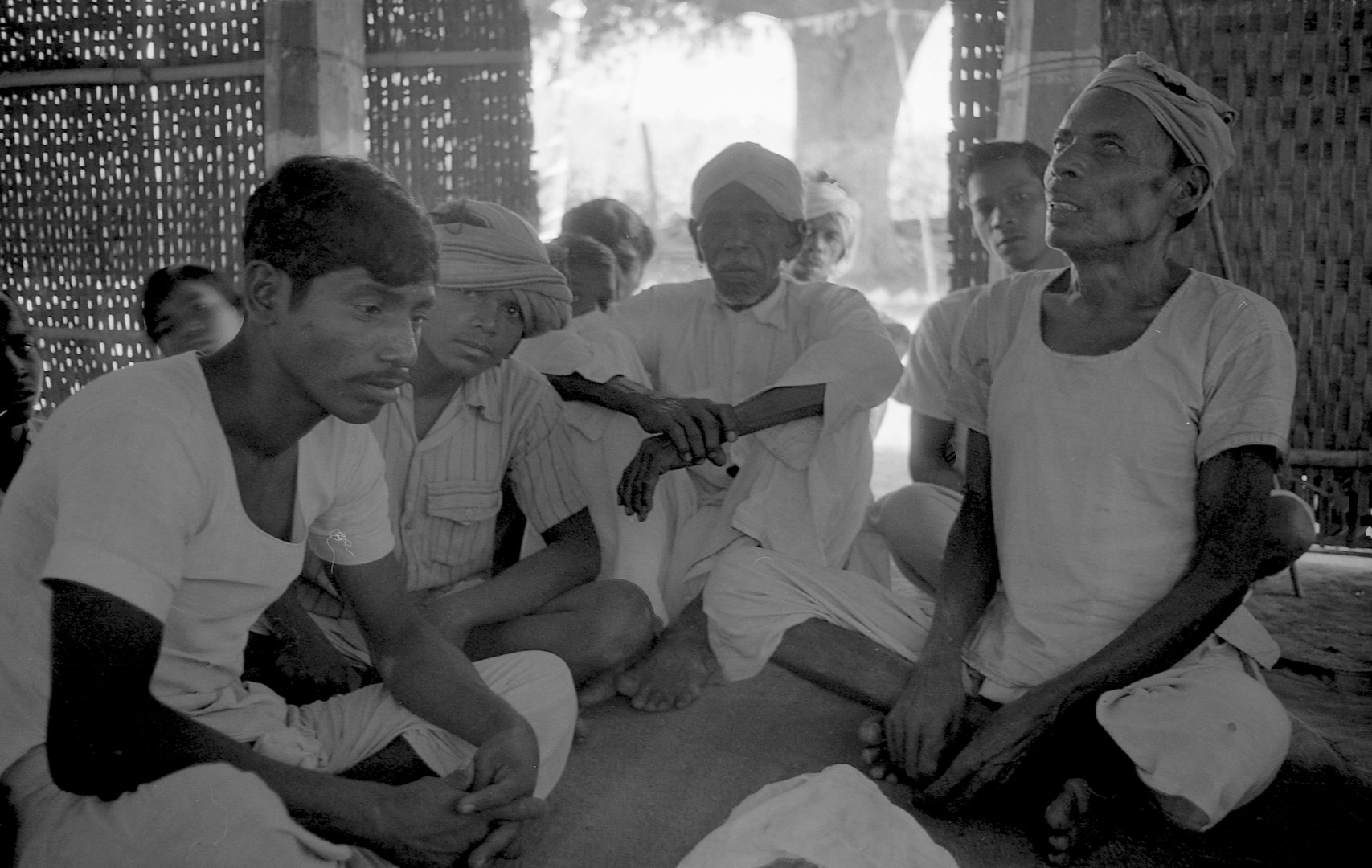

DASSERAH, the ‘Beating the Village Bounds’, is held after the monsoon harvests. It is redolent of the feudal age of the Koitur, when villages owed allegiance to their feudal lord, the Koitur Raja. It is presided over by his agent and rent collector, the ‘Deshmukh‘, along with the village priest, the ‘Katora‘, and the ‘Patel‘, the village headman. It is a ceremony of obeisance to the authority of the spiritually important feudal king, the ‘Raja‘. It defines the village territory.

A series of flags are erected where paths enter the village boundary. They plead with the village spirits to protect them from the mischievous forest spirits. They beg for a good agricultural year and, to the sound of drums, oboes and brass horns, they ceremonially walk round the village boundary.

A black and one white yak’s tail fly whisk, the ‘Chauwur‘, symbols of power and authority of the male and female aspects of the Great God, and an antique sword and spear, the ‘Sale‘, symbols of the feudal lord, are venerated. They represent village’s duty to provide military service to their overlord. It is redolent of a patriarchal system and is a largely male event defining membership of the village.

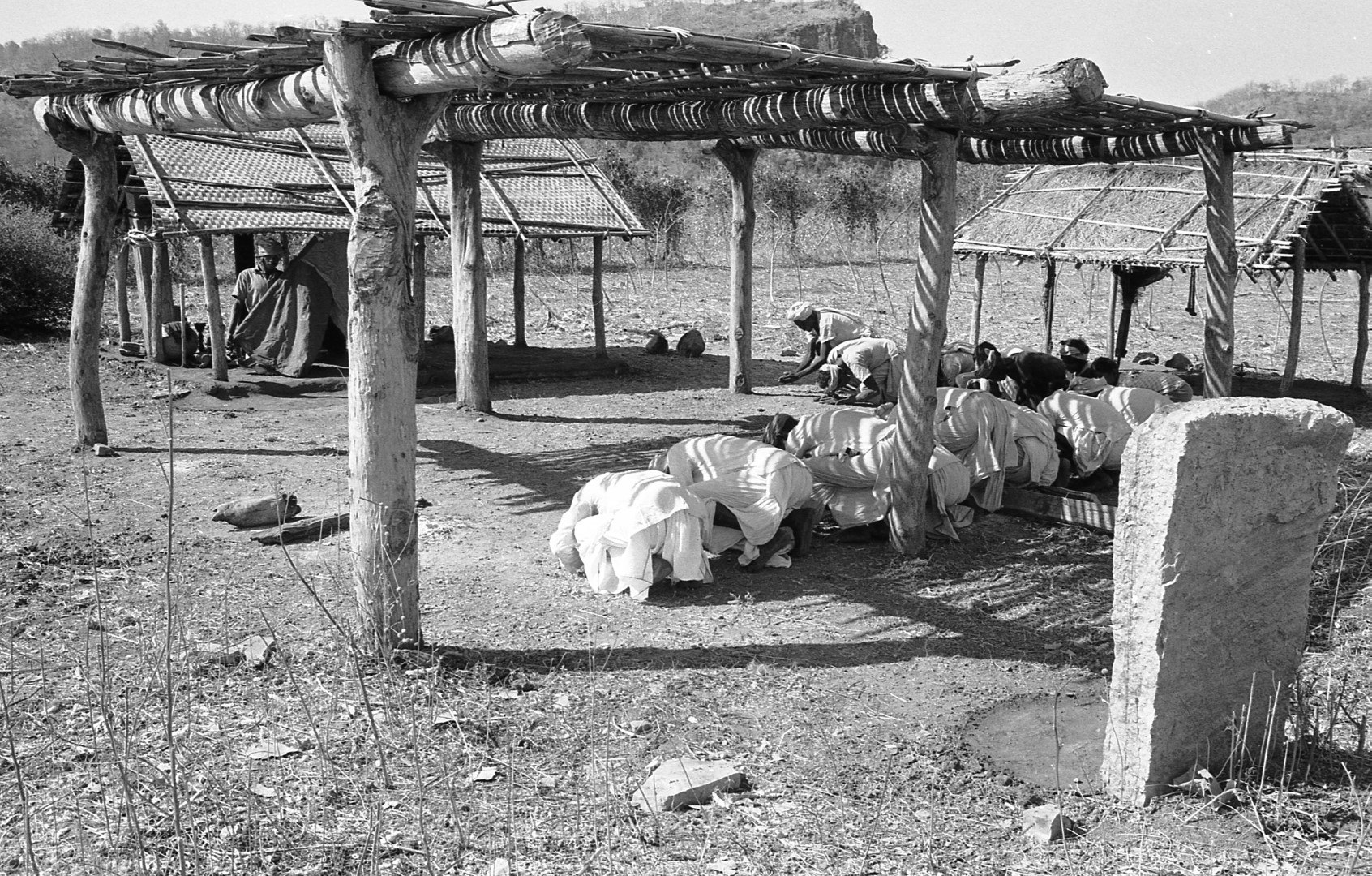

Durari and 'Podela Poymar'

This festival marks the start of the agricultural year and also every villager’s membership of the village. If a man plans to move to another location that year he will not participate in his present village festival, but in the place that he intends to live. It defines the village as a ritual and agricultural community. It is held at the same time as the Hindu festival of Holi, but bears no similarity. The village headman, whose ancestors started the settlement, takes charge.

It is the festival at which all contracts with moneylenders, servants and rental agreements are renewed. Colloquially it is called ‘Podela Poymar‘, meaning ‘cutting the undergrowth’.

In earlier times the Raj Gonds were shifting cultivators, who cleared new areas of forest when their old land had lost its fertility. However, since the Nizam of Hyderabad started registering land ownership and demanding a land tax to fund his government, he banned forest clearance and reserved the forest as a state property, rather than a natural resource for the people, arguing that this natural resource needed protection. This radically changed the Raj Gond’s agricultural techniques. They are nowadays settled agriculturalists.

However, their religious rituals are redolent of their earlier traditions of shifting cultivation. Today the Durari festival, often referred to as ‘the cutting of the shrubs’ has become a ritual defining village membership and belonging to a sacred community and the maintenance of personal contracts and agreements.

Fortune telling

Occasionally a wandering fortune teller, ‘Jadu Patuwa‘, arrives in the village with his magical cow. He is a non-tribal Hindu low caste person. He lives by charging for his cow to tell peoples’ fortune. They ask the cow a question and the cow answers by tapping its foot, which the fortune teller then interprets. However, the Raj Gonds, being ‘adivasi‘ tribals with a different religion, largely ignore him’

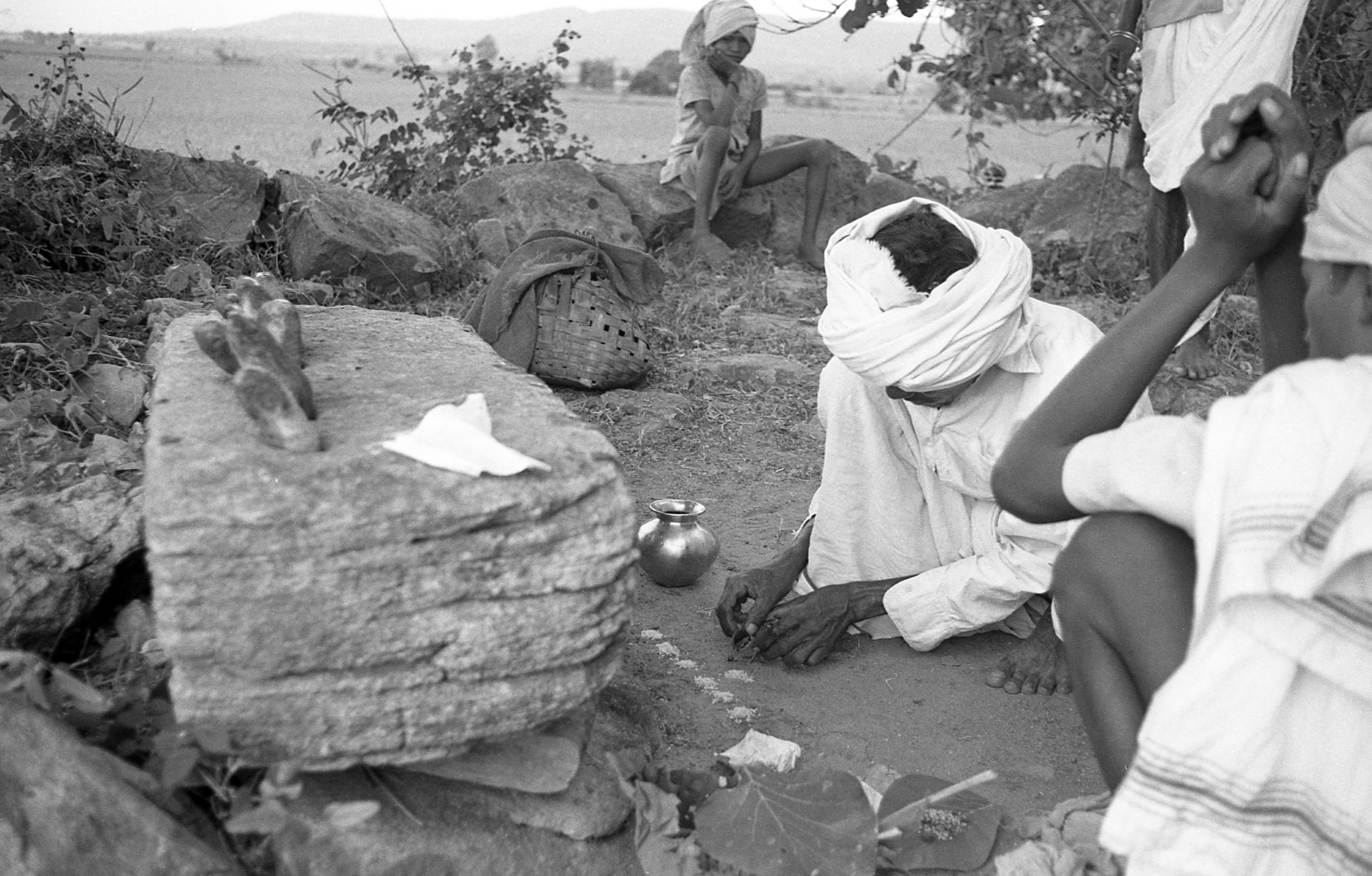

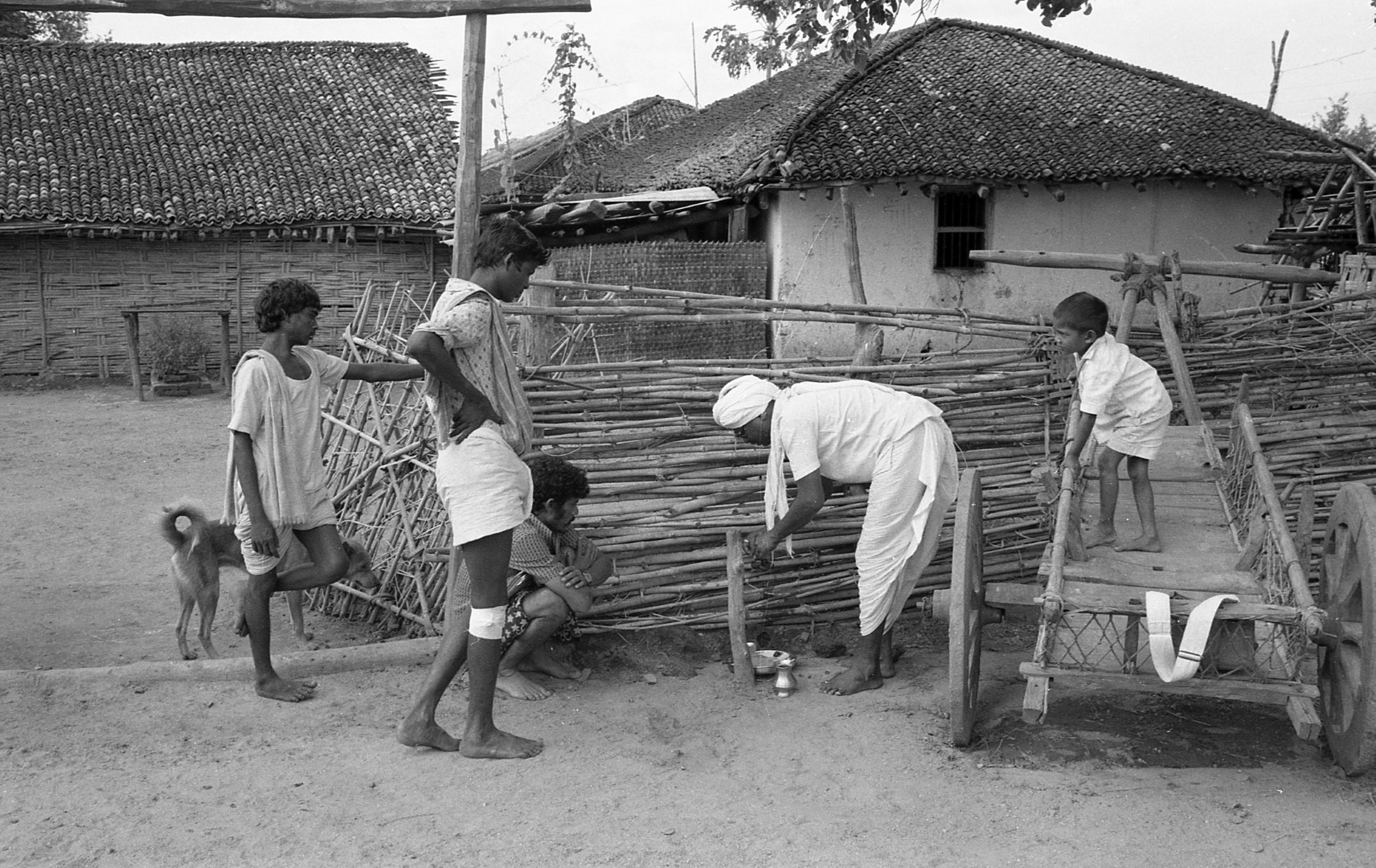

Funerals Cremation, 'Mod Sabha'.

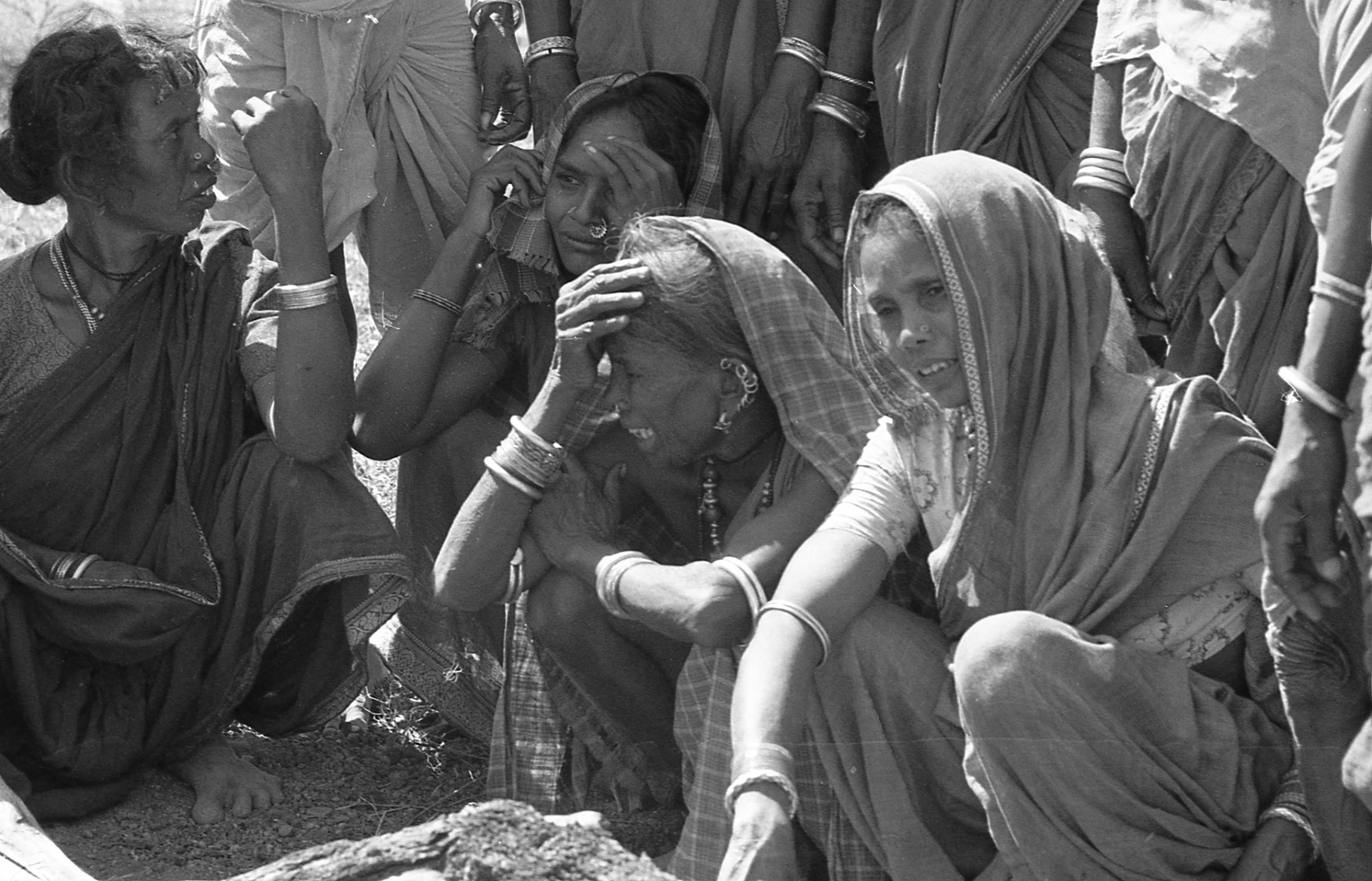

Death is a deeply emotional time, not only for close relatives, but also for the whole community, who show their misery by removing one wheel of their bullock carts.

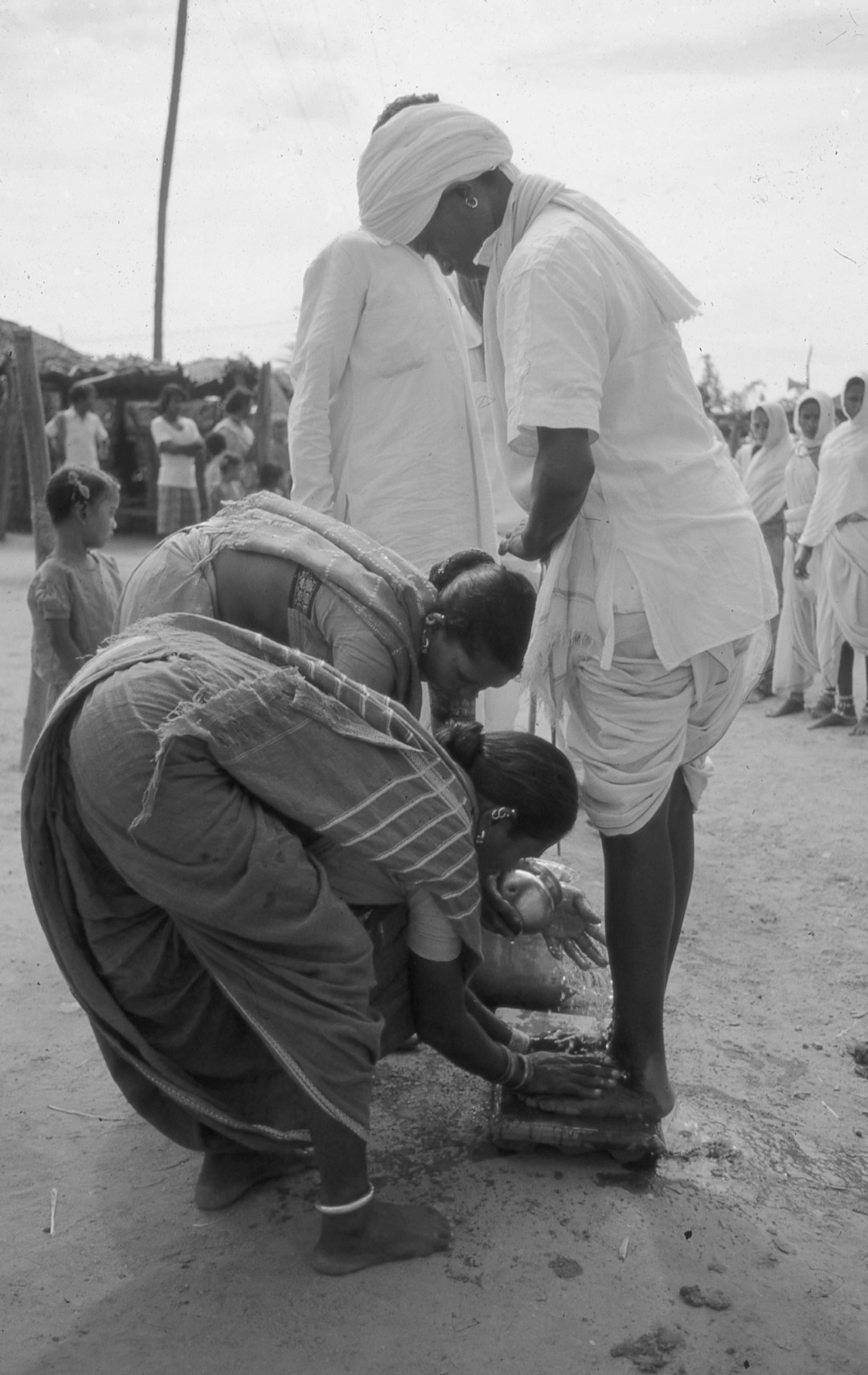

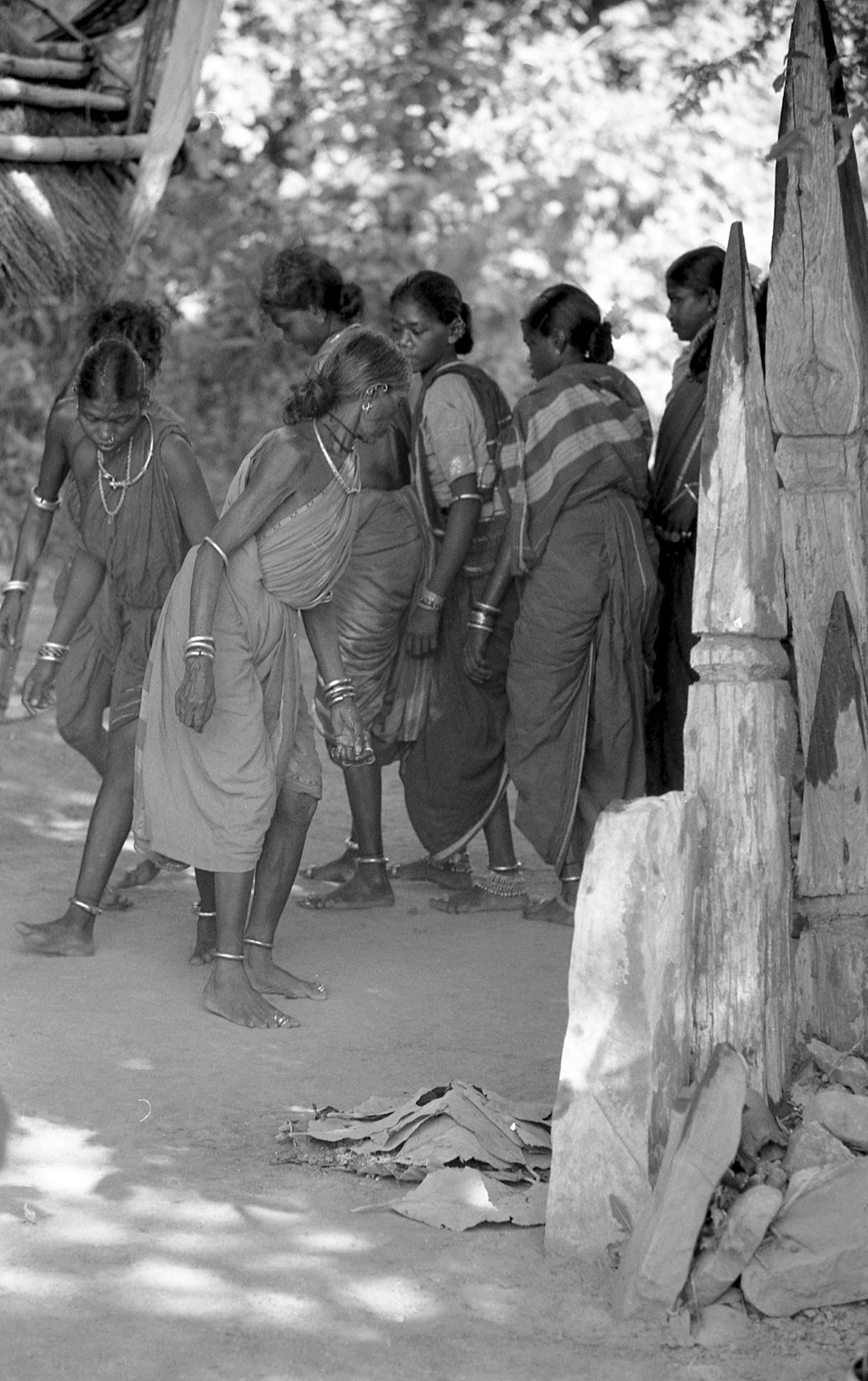

The body of the deceased is washed, oiled and carried to the cremation ground on his upturned cot, ‘charpoy‘. Each leg of the cot carries a white flag of mourning. His wife, daughter and granddaughter weep.

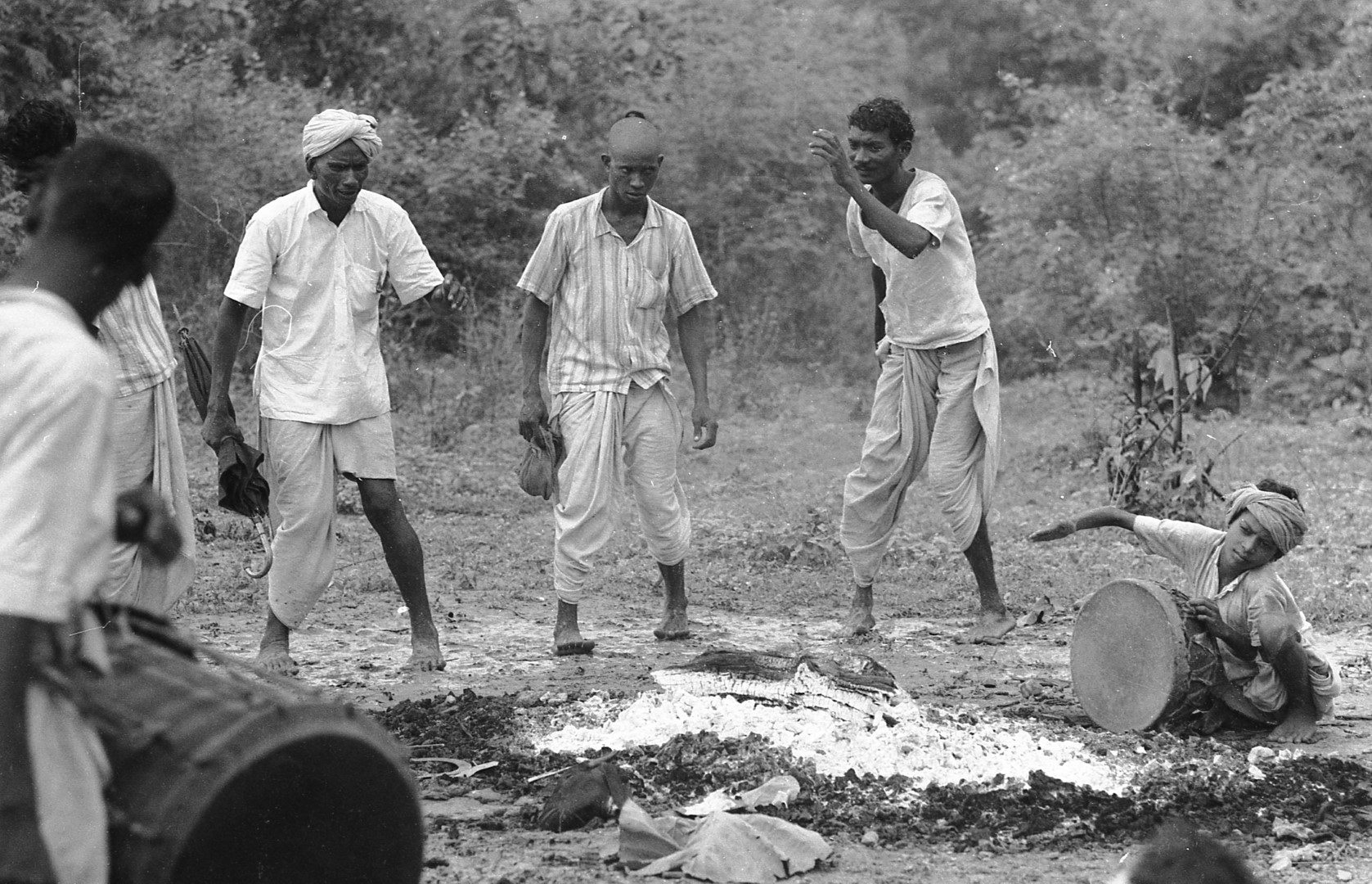

The cremation is performed in silence. But when the ashes are carefully assembled the deep sound of drums and oboes drowns out all emotion. Then the clansmen’s minstrels, the ‘Pardhans‘, chant the ‘sana patta‘, the song of the ancestors. They remind everyone of the legendary story of the world’s creation and how Bhagwan gave life to mankind. It recounts the life of the original clansmen, their direct ancestors. It is a time to reconnect with the everyday life of the living.

Normal life is finally re-established with a feast, the ‘Mod Sabha‘, given to the people of the village community.

Finally, the close members of the family symbolically bathe themselves in public, washing away the impurity of death.

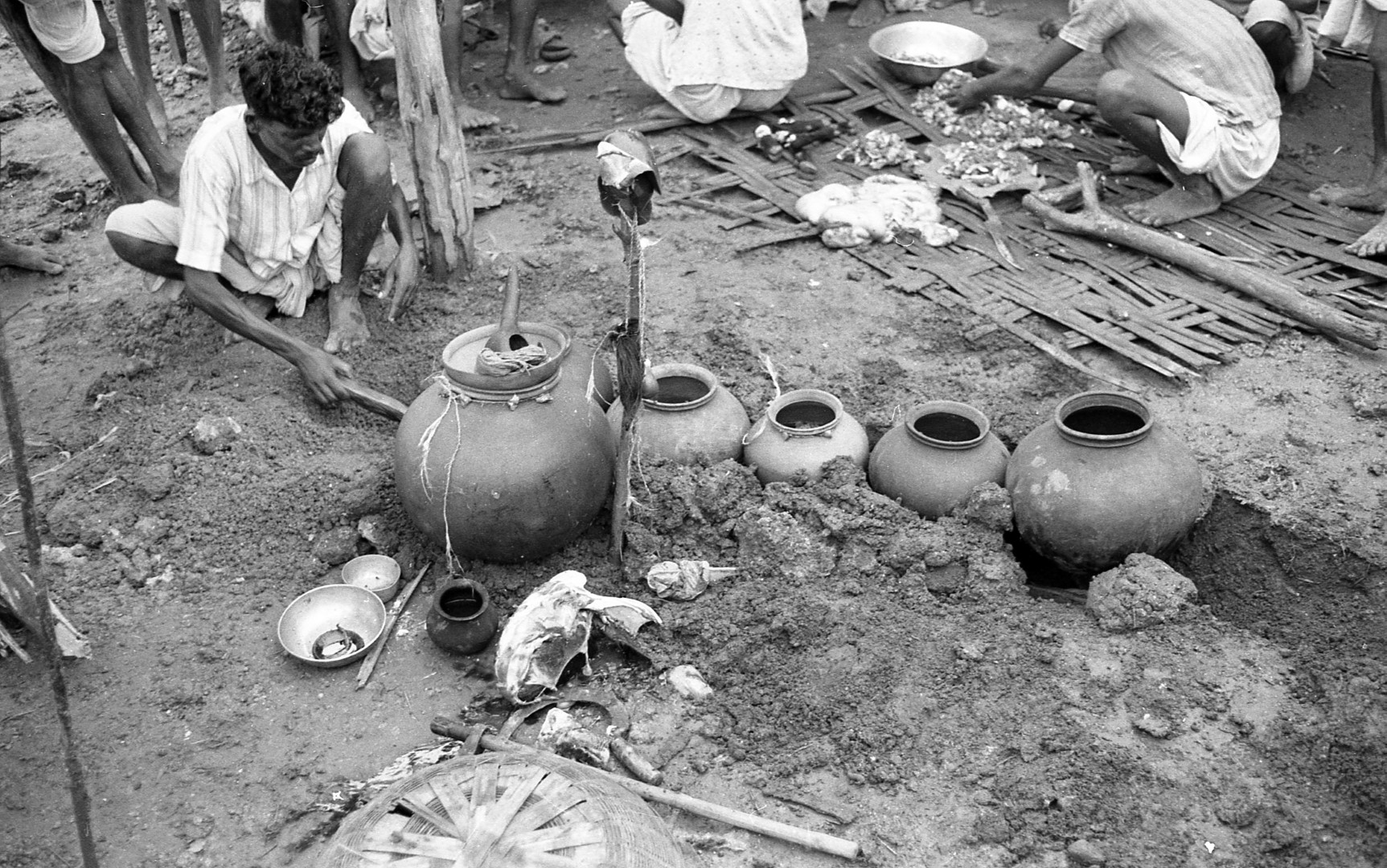

After the cremation they return to the house for a ceremony called the ‘Mod Sabha‘ where a goat is sacrificed to the five elements that make up all matter, earth, air, fire, water and spirit. Finally, a feast of celebration for his life is held, while the minstrels, Pardhans, sing about creation, his clan origins and the nature of existence.

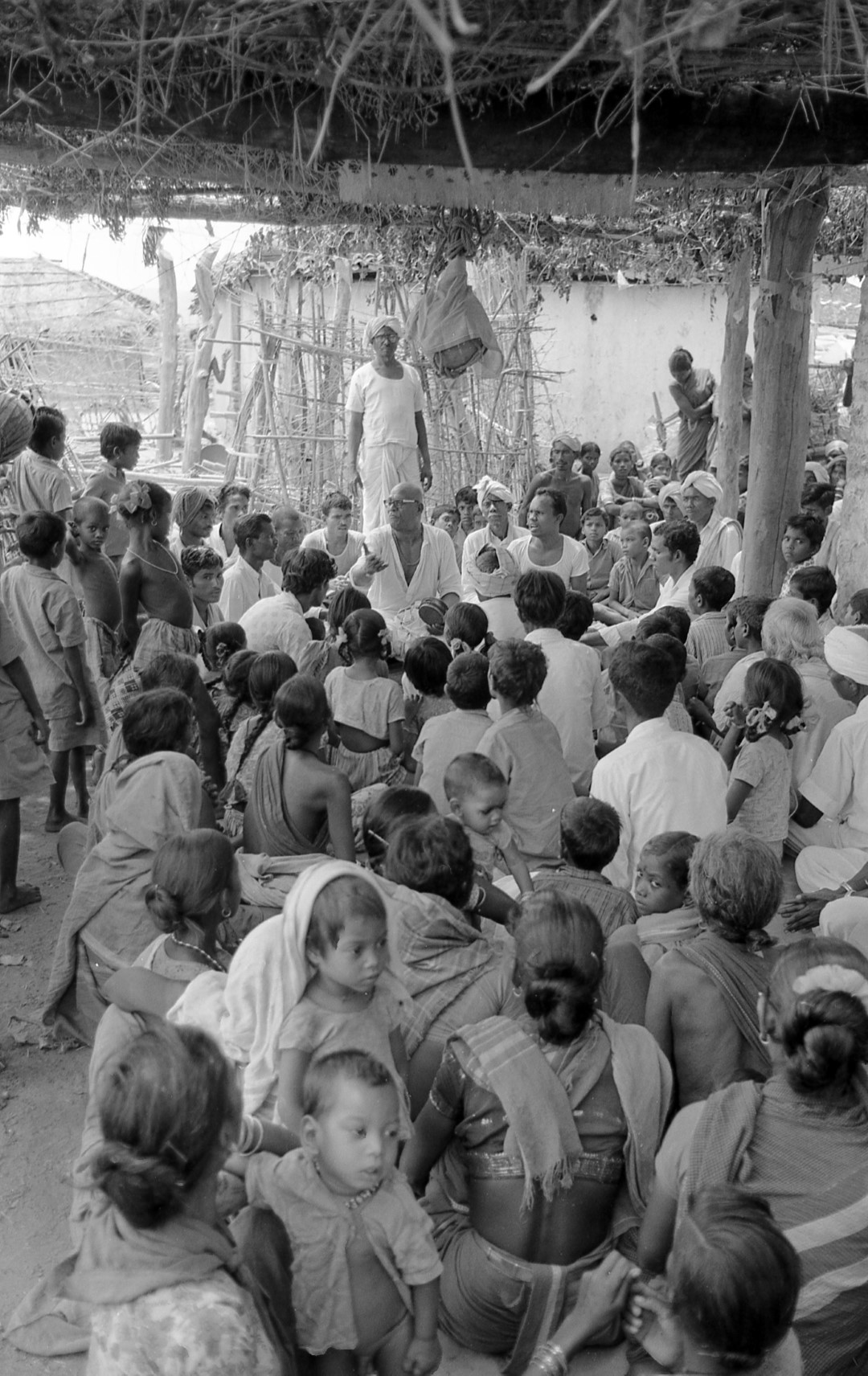

Hindu reform movement, Surojee Maharaj

In the 1970s a Hindu reform movement lead by Suroji Maharaj became popular among the ‘adivasi‘ Raj Gonds. This was a passionate Vaishnavite bhakti devotional cult. Many Raj Gonds followed it, feeling that it increased their status as a marginalised group.

Jangu Bai

Every Raj Gond village has a shrine to the apical ancestral goddess called Jangu Bai. Not unlike the Christian worship of the Virgin Mary, she is a mother Goddess of the traditional Raj Gond belief system. She is one of the ancestral spiritual protectors.,

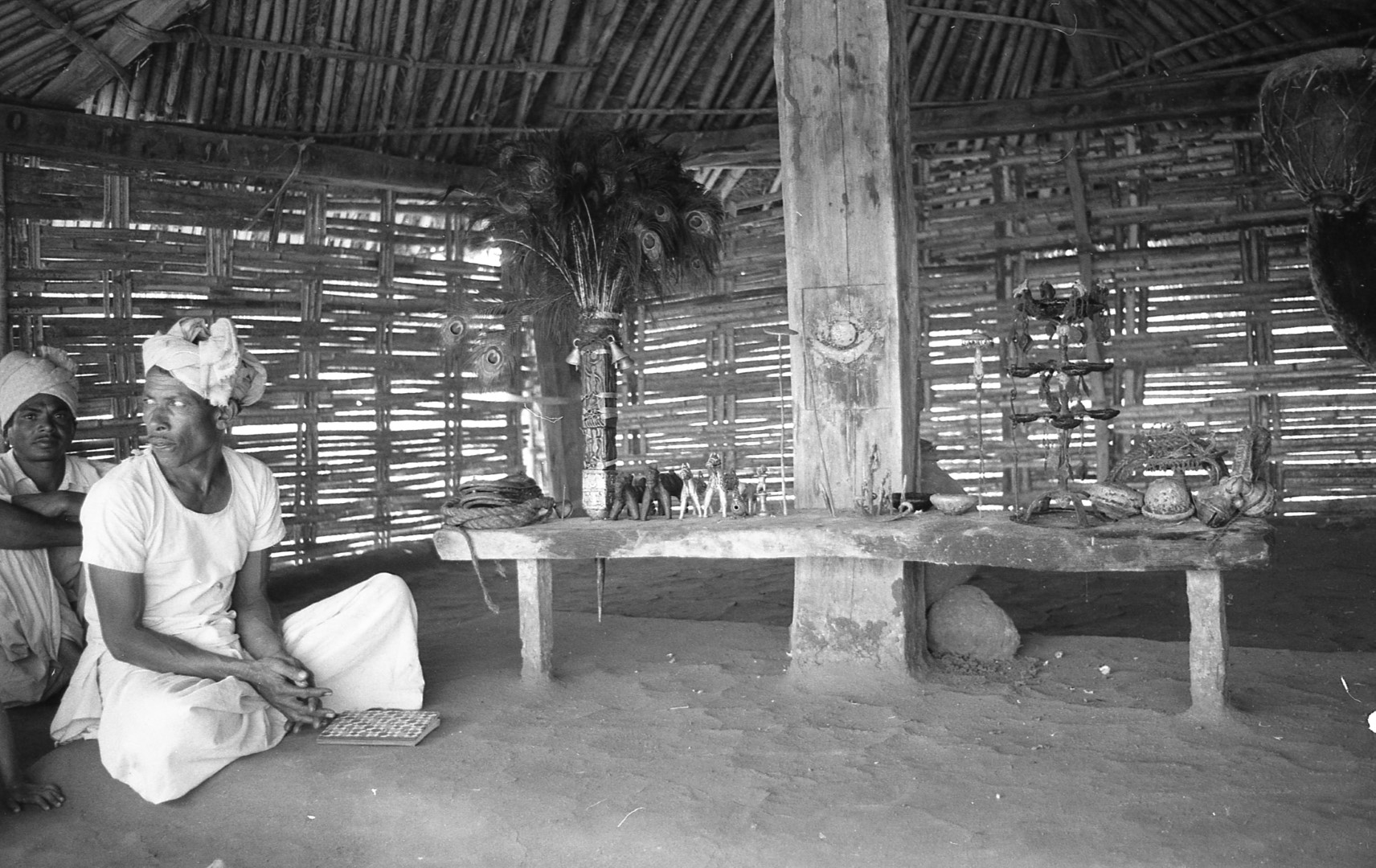

Persa Pen

The great founding ancestor of the Raj Gonds, Pahandi Kupar Lingal, told his people that each of the original four phratries, ‘Saga‘, should worship their own deity, called ‘Persa Pen‘ or Great God. However even though each phratry has its own ‘Persa Pen‘ they are all considered the same god.

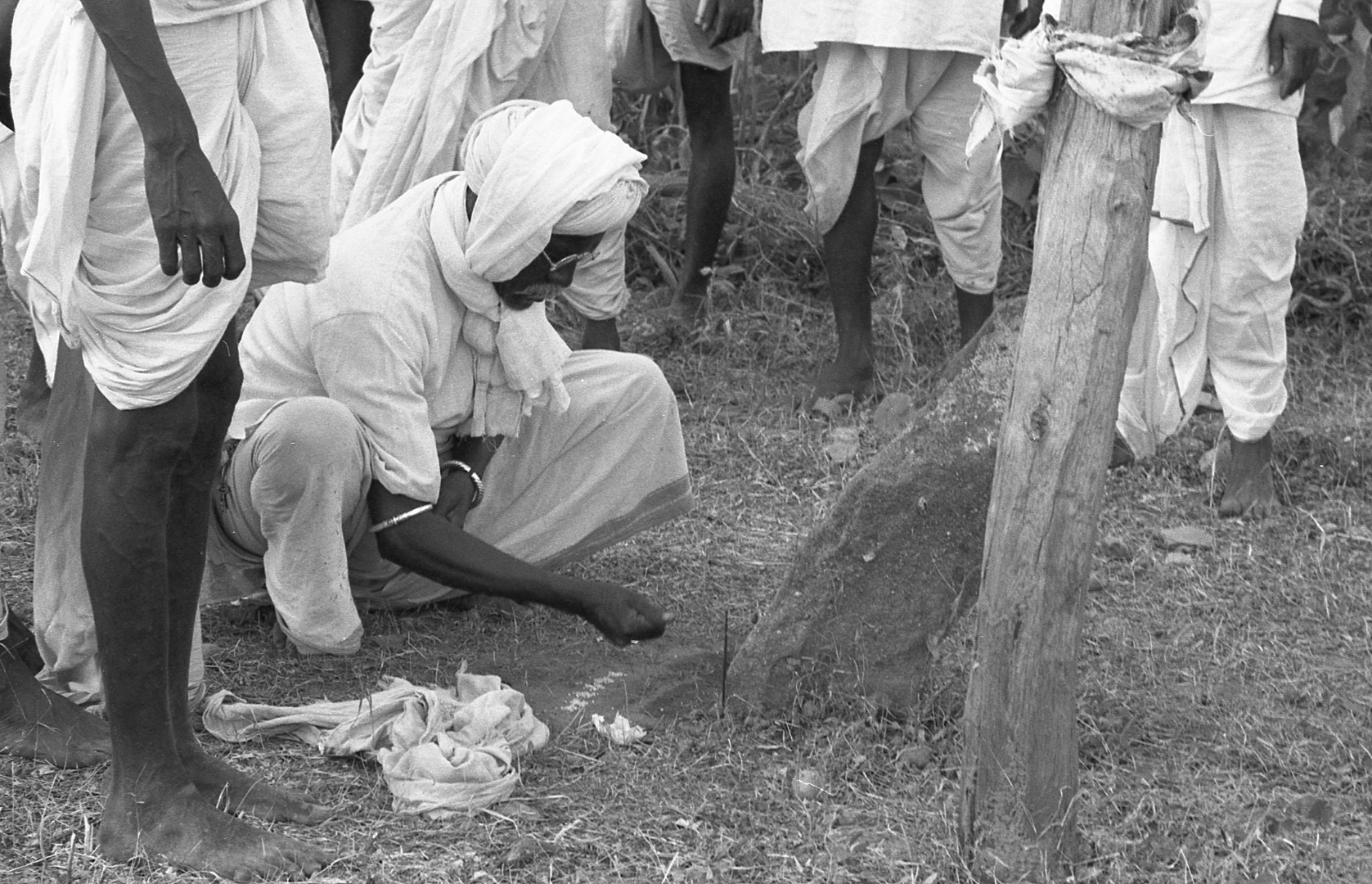

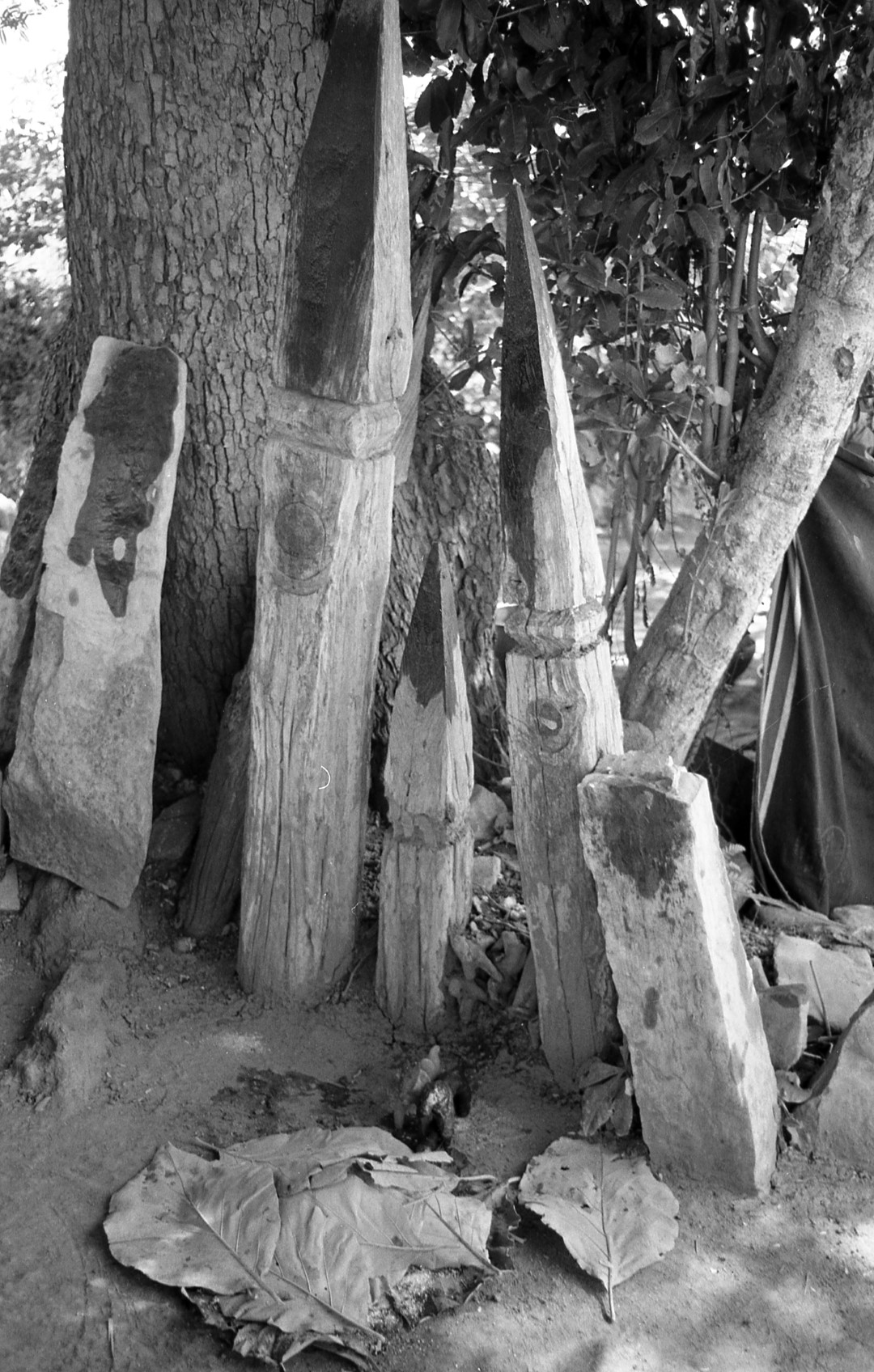

Every village has a ‘Persa Pen‘ shrine, at which all the phratries perform their rituals. Once a year the villagers gather for an ecstatic ritual when the men go into a state of possession and trance, during which they are whipped by the village priest to show their devotion to their clan deity. This deity is seen as the protector of his people. His shrine is usually near the centre of every village. He is always represented by a ‘kamk‘, a tall square wooden post with a pointed head. Engraved on it is a crescent moon lying on its back and holding up the circle of the sun.

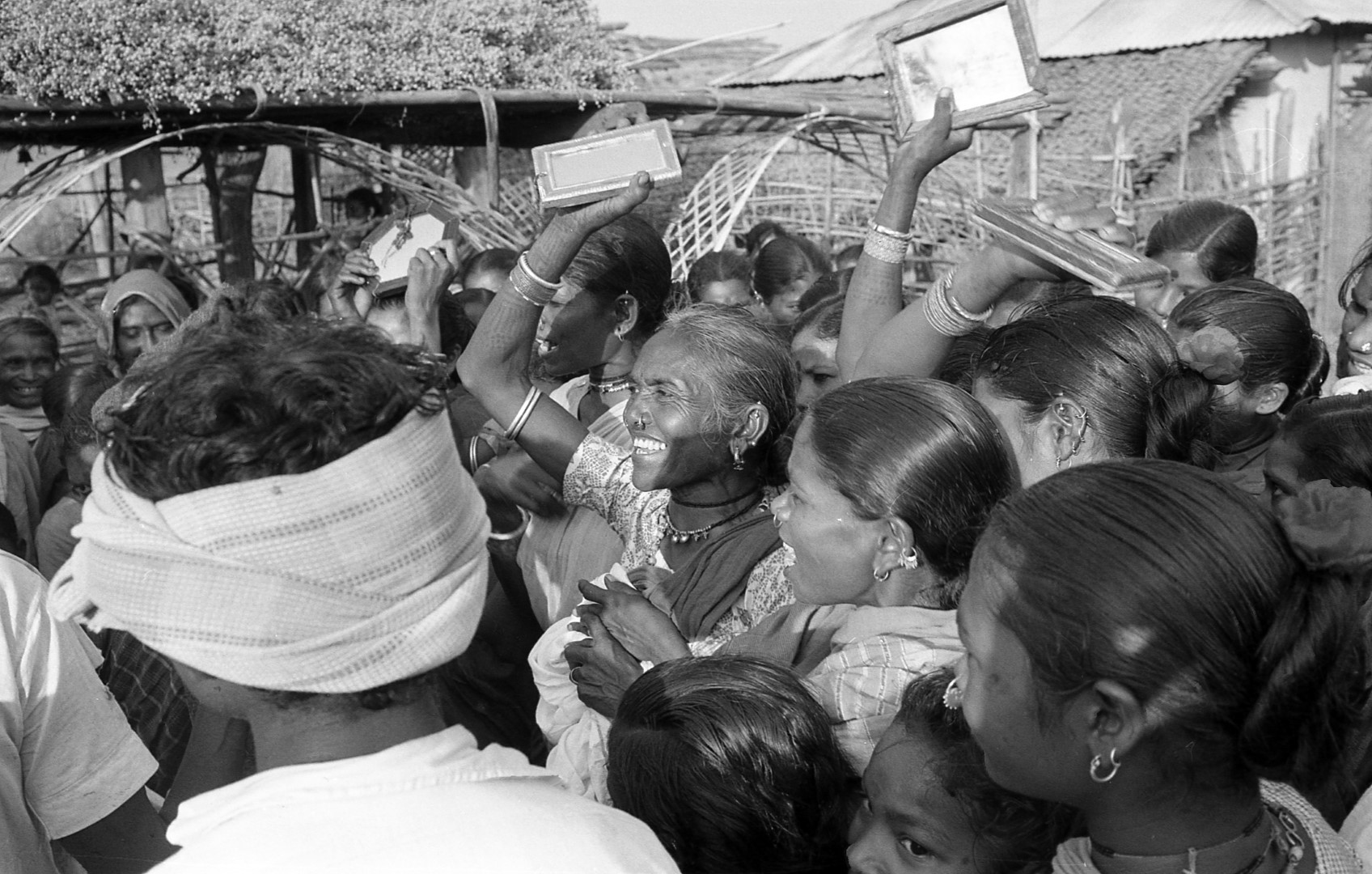

Other than the mythical founding father of the Raj Gonds, ‘Pahandi Kupar Lingal‘, who is not worshipped as a deity, ‘Persa Pen‘ is the central deity worshipped by all Raj Gonds. To be a Raj Gond is to be a follower and devotee of ‘Persa Pen‘. Every household will have a framed image of ‘Persa Pen‘ displayed in the main room of the house.

The great feast of ‘Persa Pen‘ is held in the month of Bhawe, May-June.

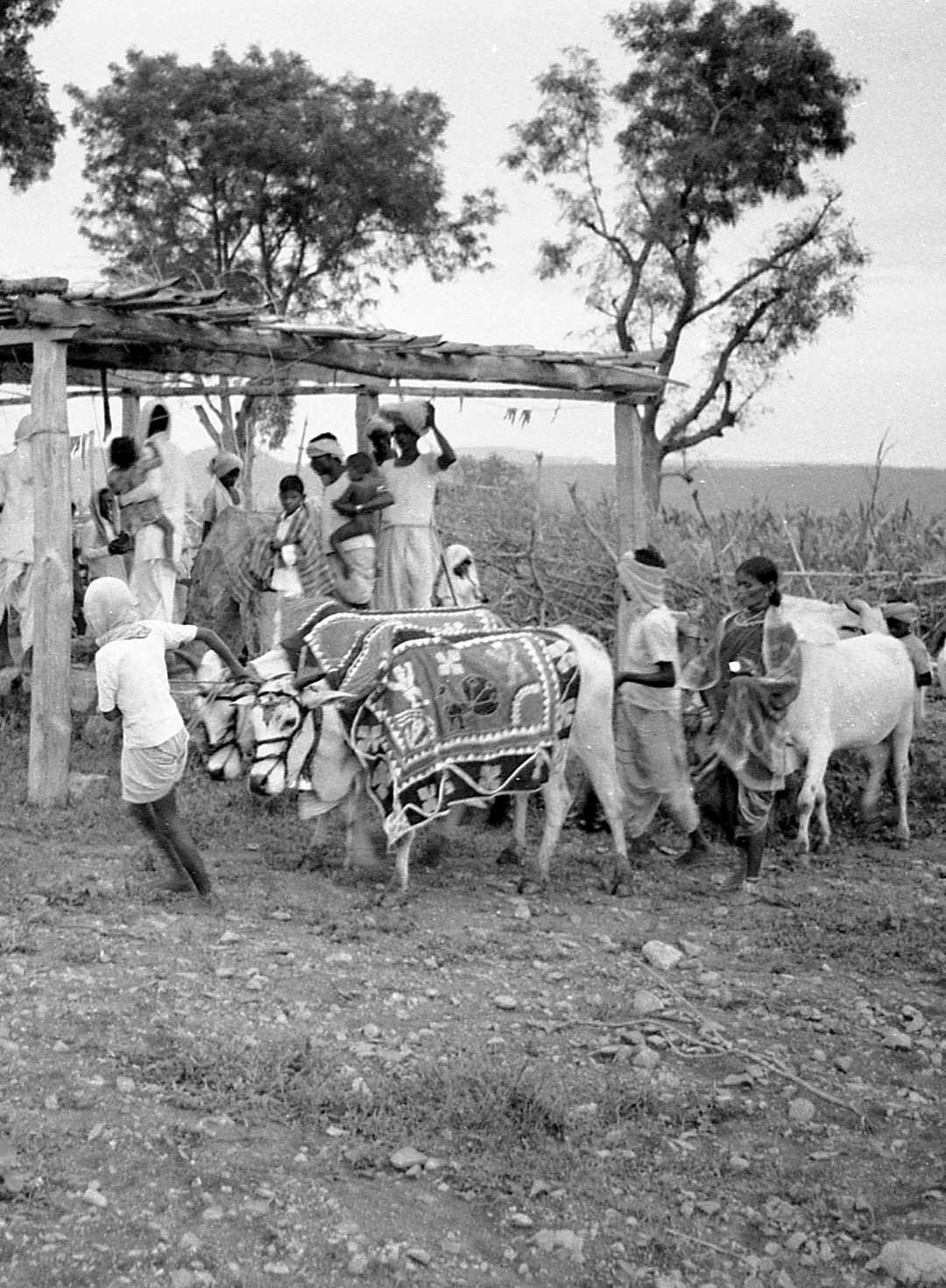

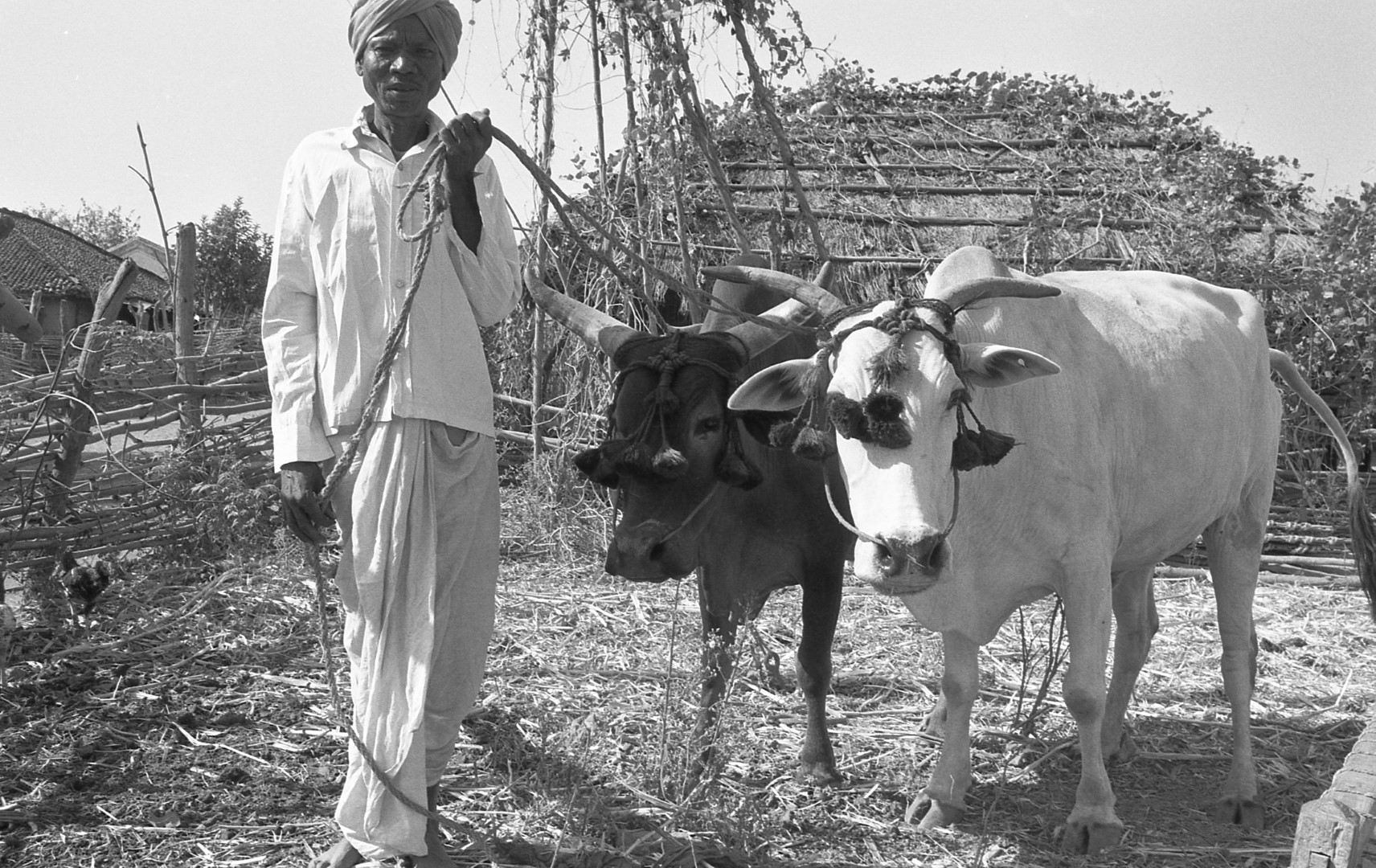

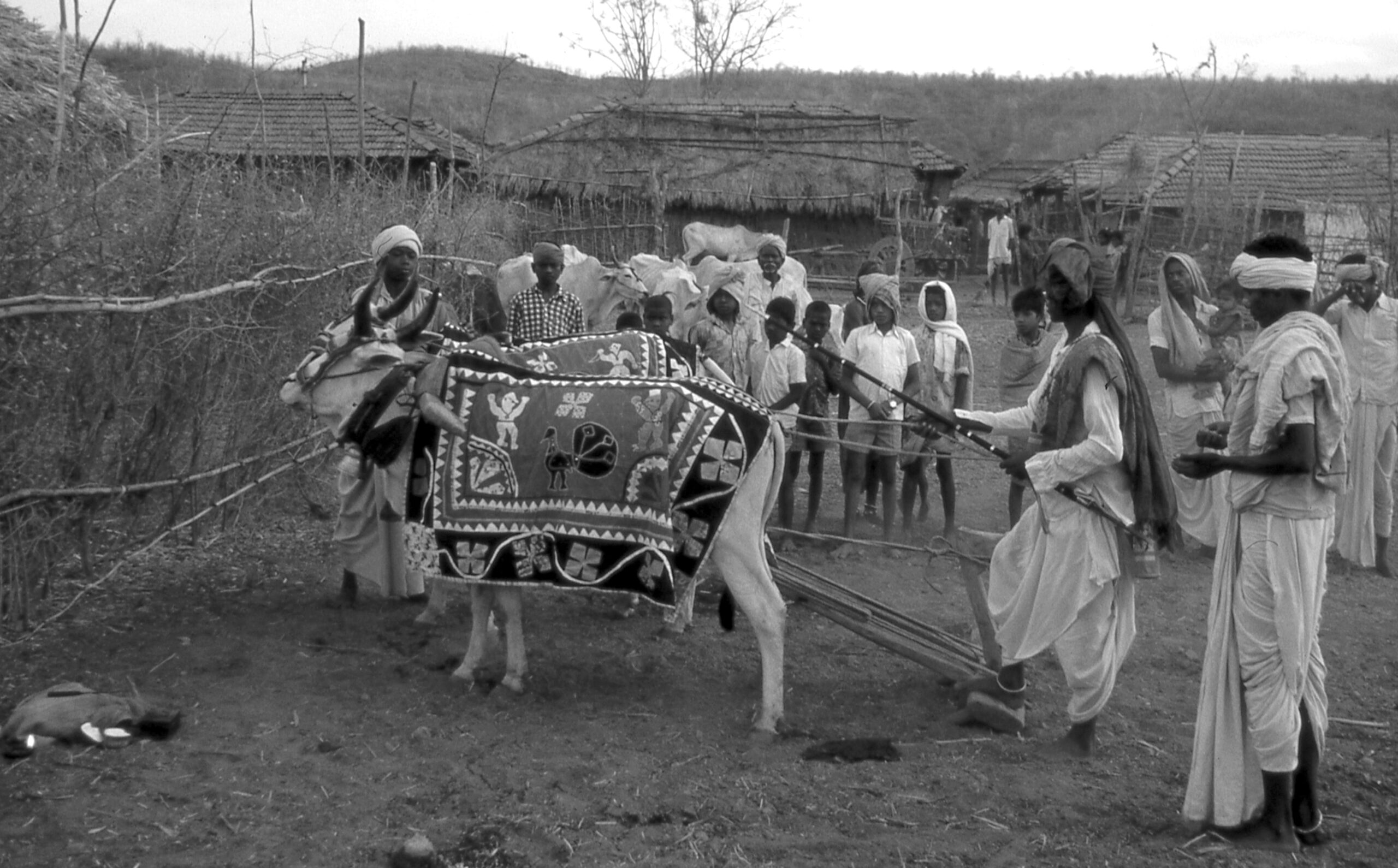

Pola Puja, Cattle worship

This festival is held in July and August at the end of the monsoon season. It honours and protects the villager’s plough bullocks on which the Raj Gonds depend for ploughing their fields and hauling their carts, an essential role in their agricultural economy.

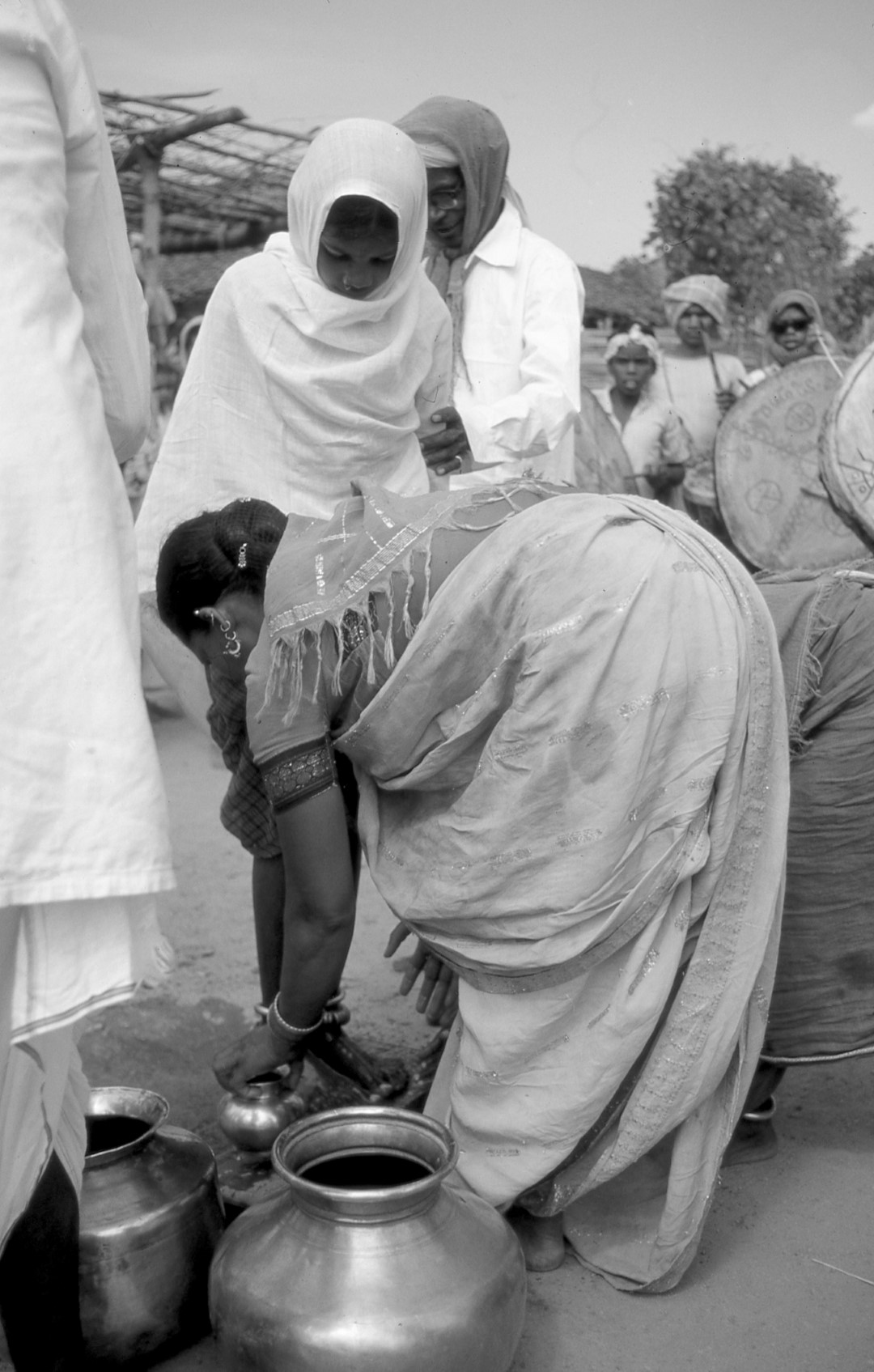

Each household dresses their best pair of trained draught bullocks in embroidered blankets and takes them to the shrine of the Village Mother, and the Earth Mother, ‘Dodi Marke‘. As plough cattle their job is to impart fertility to the soil, to Mother Earth, and to bring prosperity to the people. Therefore, they need the protection and blessings of the ‘Siwa Auwal‘, Village Mother goddess.

The bullocks are then taken back to cattle sheds by their owners, attached to their ploughs, and, in front of a small shrine, where coconuts have been broken, they are fed sweetened and fried oatcakes, as a treat in gratitude and in their honour.

The children of the village then mount high bamboo stilts and go round the village beating the posts of the house and going to the village boundary asking for protection of ‘Siwa Marke‘, the goddess of the boundary.

This is a festival of joy and fun assuring people of a fruitful harvest and a bountiful year.

Siva Bori

This is a small family ceremony to ‘Siwa Bori‘ the boundary goddess of their land.